What has inspired this post are some comments made by reviewers of a paper, of which I am a co-author (essentially, I provided the data and Dr Will Jones the analysis), submitted for publication. The reviewers were generally positive but raised a few questions which we are addressing. However, this had me reviewing the data I have provided for the paper, and then looking beyond. This analysis is outside of the scope of our submitted paper, so there is no conflict with that potential publication.

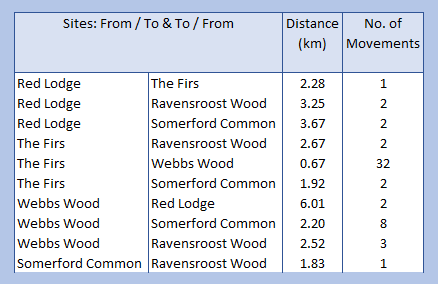

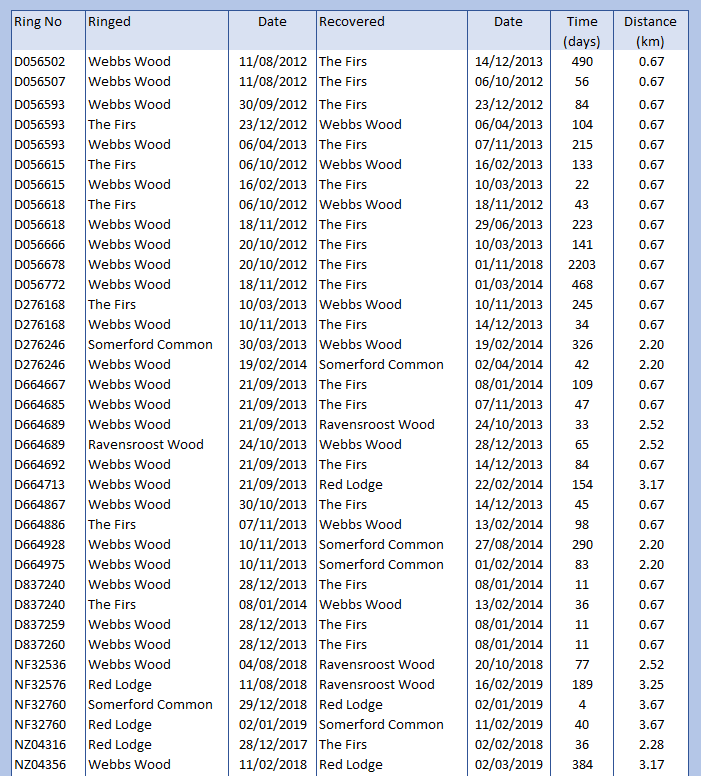

The first thing that struck me was that one reviewer picked up on the fact that my ringing team have the record for the second longest movement of a Blue Tit within the UK. This bird, ring number AVF6109, was ringed at Fort Augustus in Highland on the 31st December 2019 and recovered by us on the 9th January 2022 in Ravensroost Wood: a distance of 639km in 740 days. From this the reviewer questioned the frequency of movements of Blue Tits in and out of the Braydon Forest. To investigate this further, I have done an analysis of Blue Tits ringed in the Braydon Forest and retrapped in other parts of the Forest, to get an idea of the movements within the area. In addition, I have also analysed the movements into the Forest from outside, and from within the Forest out to other sites. Obviously the last of these is dependent on us receiving recovery reports of Blue Tits we have ringed being caught or found elsewhere. The vast majority of the movements are within the Braydon Forest. I have counted all movements, including several where the bird moved from one site to another and then back again. Between 1st January 2013 and 31st December 2023 there were 70 movements within the Forest, i.e. 6.3 movements per year. However, 56.5% of those were movements between the Firs and Webb’s Wood and vice versa: a distance of less than 1km between two woodlands separated by a road (Wood Lane).

Table 1: Summary of Blue Tit Movements in and around the Braydon Forest

Table 2: Detailed movements of Blue Tits in and around the Braydon Forest

In addition to these movements we have had, in 11 years, just three records of recoveries of birds that have been ringed in the Braydon Forest and recovered elsewhere: one at one of my other sites: Lower Moor Farm, one in the nearby village of Brinkworth, and the other at the nearby town of Royal Wootton Bassett:

Table 3: Detailed movements of Blue Tits out of the Braydon Forest

The Brinkworth bird is the only one that was recovered dead, the other two were retrapped by my team (Lower Moor Farm) and the North Wilts Group.

As for birds moving into the Braydon Forest: as well as the aforementioned Scottish bird, we have just three other records of birds that we have retrapped in our nets that were ringed outside of the Braydon Forest and recovered within it:

Table 4: Detailed movements of Blue Tits into the Braydon Forest

To put this into perspective: over this same period of 11 years we have ringed 4,787 Blue Tits. The number of recoveries within the Forest represent less that 1.5% of the total number of birds ringed within it, and less than 5.9% of all recaptured birds: i.e. 94.1% of retrapped birds are recaptured in the same part of the Forest as they were ringed in. If we look at movements greater than one kilometre the figures become even more reduced: less than 2.6% of all recaptured birds outside of those moving between the Firs and Webb’s Wood have been caught away from the site at which they were ringed. Those birds moving into or out of the Forest do not really warrant any sort of percentage allocation.

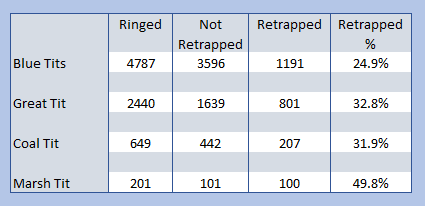

One other question that always arises is the validity of the recapture data that we have. I have calculated the number of birds ringed, the number of individuals that are not recaptured and the number of those individuals that are recaptured. This I have done for each of the four species of Paridae in the Forest:

Table 5: Numbers of Paridae Processed in the Braydon Forest

The retrapped proportion is the number of individual birds that have been retrapped, divided by the total number ringed. Each retrapped bird has been counted only once, no matter how many times it has been recaptured. I think that it is important to note the proposed mortalities of these species. The key example is the one with the most data, the Blue Tit. Do we recapture fewer Blue Tits because they move on elsewhere after ringing? We are getting virtually no evidence of this from ringing recoveries. Is it because so many of them are dying? According to the data accumulated and presented in the BTO’s BirdFacts analysis, first year mortality in Blue Tits is in the region of 62%, as is the case with Great Tits. Adult mortality in Blue Tits is typically 47% year on year: adult males have lower mortality at 49%, with adult females at 58%, so there is a considerable die-off which must impact on recapture rates.

Marsh Tits are known to be the most sedentary of the species, so the highest recapture rate is not surprising. What this data doesn’t tell us is what influences the level of the recaptures. There is not enough data on Coal Tits to be able to provide an estimate and Marsh Tits apparently have a first year mortality of rate of 81%! If that is the case, it is no wonder that they are a red-listed species. Anyway, the paper that we are working on is looking into mortality rates of the titmice in the Braydon Forest, so I will say no more about that in this blog.

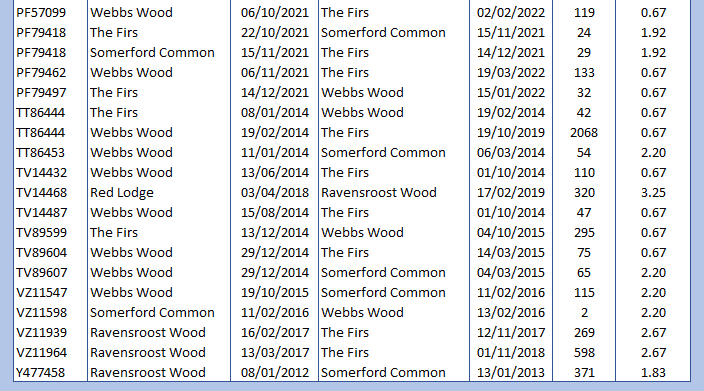

What I will say is that I have carried out an evaluation of the movements of the other three species in and around the Braydon Forest. The Great Tit is the only other species that shows any significant movements:

Table 6: Summary of Great Tit Movements in and around the Braydon Forest

Just like the Blue Tits, the movements between the Firs and Webb’s Wood and the reverse are far and away the biggest proportion: 58.2% of all movements. The number of Great Tits moving more than once between sites is actually higher than in Blue Tits, with 10 of them doing so, compared to just three Blue Tits. One of them, D056593, is quite peripatetic: Webb’s Wood to the Firs to Webb’s Wood to the Firs.

Table 7: Detailed movements of Great Tits in and around the Braydon Forest

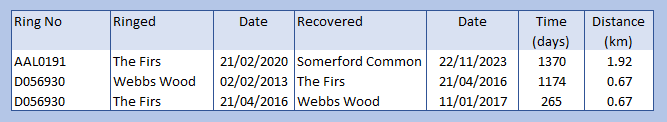

There were just two movements into the Forest:

Table 8: Detailed movements of Great Tits into the Braydon Forest

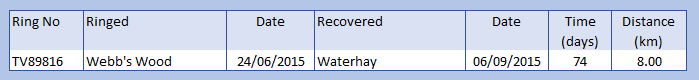

We have had just one reported recovery from outside of the Forest:

Table 9: Detailed movements of Great Tits out of the Braydon Forest

Coal Tit movements are very few and far between:

Table 10: Detailed movements of Coal Tits in and around the Braydon Forest

And, somewhat unsurprisingly, Marsh Tits have even fewer:

Table 11: Detailed movements of Marsh Tits in and around the Braydon Forest

We have absolutely no records of any movements into or out of the Braydon Forest for either of these two species.

As you can probably guess, I didn’t get out to do any ringing this weekend due to illness. I am not sure that this helped with the crippling headaches that kept hitting me, but it passed the time in between.