Having done a considerable amount of analysis on the Paridae within the confines of the Braydon Forest, I thought I would start carrying out some additional analyses covering other species, starting with the commonest of our thrushes, the Blackbird. Over the last 24 months I have had the feeling that their numbers in the catch have been decreasing, so I wanted to see whether the figures would bear that out.

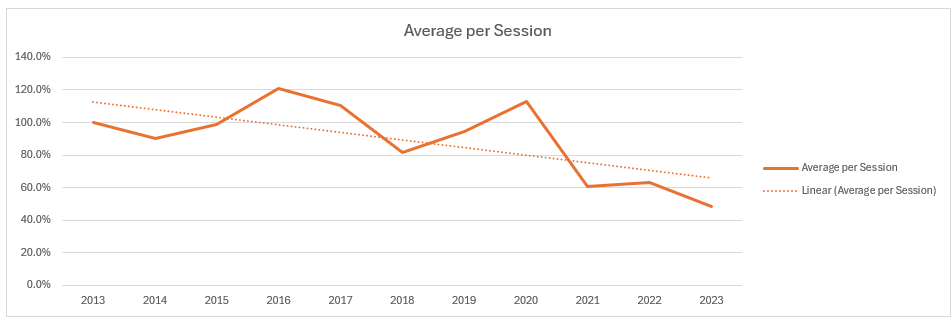

The first thing I looked at was frequency with which we catch Blackbirds:

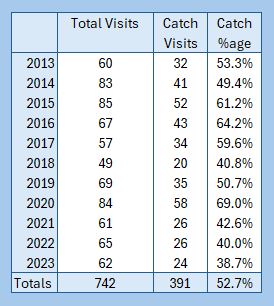

Table 1: Frequency with which Blackbirds have been caught in the Braydon Forest as a proportion of the total number of sessions over time

Graph 1: Frequency with which Blackbirds have been caught in the Braydon Forest, as a proportion of the total number of sessions, showing the trend over time

As is clear, the overall trend is downwards. How does the catch frequency compare with the other species that I recently calculated?

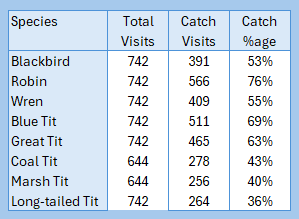

Table 2: Comparison of catch frequencies with common resident species

The Marsh Tit and Coal Tit figures are based upon a lower overall session count as neither species is found at Blakehill Farm.

So, the Blackbird is caught in just over one in every two sessions, comparing well with the Wren, but somewhat lower than the Robin, Blue and Great Tit.

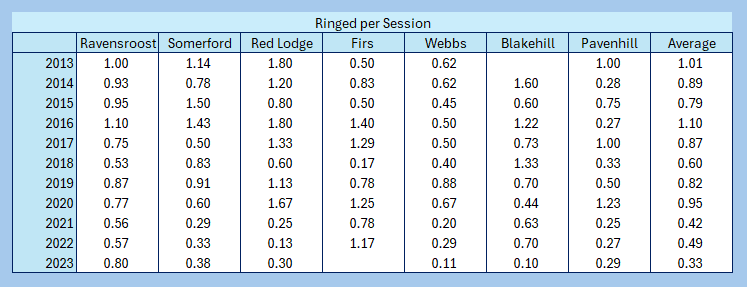

The basic catch figures are shown in the following tables:

Table 3: Number of Blackbirds ringed by year plus proportion ringed per session

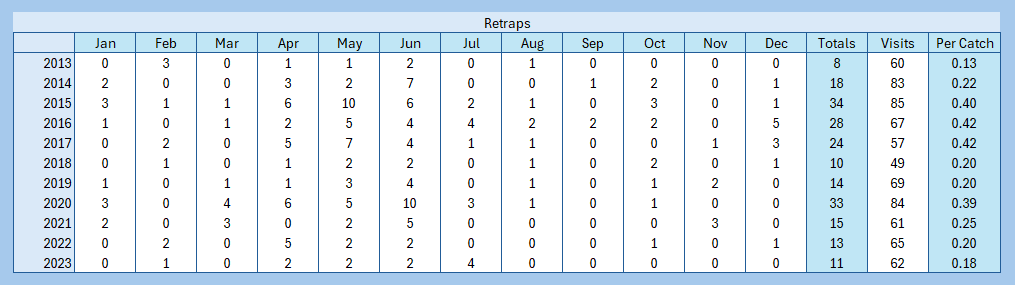

Table 4: Number of Blackbirds retrapped by year plus proportion retrapped per session

The bald numbers don’t tell the whole story, which is why I have analysed the numbers broken down by the total number of sessions, as per the end column. This gives the following graph:

Graph 2: Blackbirds ringed and retrapped divided by the total number of ringing sessions

What is clear from graph 2 is that the number of birds being recaptured is relatively stable, just a slight decline, whereas the key element in the decline of the catches is in the number of birds being ringed. Obviously, 2013, being the first full year of study across the entire Forest, has the lowest incidence of recaptured birds. This might explain the slight decline, although the lower catches in 2022 and 2023 has almost certainly added to that.

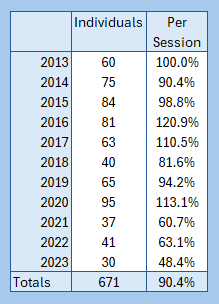

The next thing that I looked at was the actual number of individual birds caught each year:

Table 5: Proportion of individuals processed per session by year

Individual birds are birds ringed and recaptures but counted only once in each year that they are caught. Looking at table 5, there are some interesting figures there. When you put them into graphical form, the difference looks even more stark:

Graph 3: Number of individual Blackbirds processed by year

Graph 4: Proportion of individual Blackbirds processed by session by year

As you can see, despite the huge spike in 2020, the overall trend is down, but the reduction is less stark when looked at by session. So then I thought to have a look at the numbers ringed by age: to see if the reduction is age specific. I split them into: adults, juveniles and 2nd year birds. Juveniles being birds fledged in that calendar year; second year birds fledged in the previous calendar year and everything else was classified as adult.

Table 6: Numbers of birds ringed by age group by year

Graph 5: Numbers of birds ringed by age group by year with trendlines

As is clear from graph 5, the reduction in the catch is across all age groups but least pronounced in adults and most pronounced in juveniles.

With the precipitous decline within the last three years, I decided to have a look at the results if I removed those years from the analysis:

Graph 6: Blackbirds ringed by year and by session between 2013 and 2020 inclusive

As you can see, the 2020 spike counteracts the 2018 trough, and the decline is significantly reduced. The question has to be: what has sparked such a decline in the last three years? I wish I knew the answer, so I decided to see if the decline is across the board or focused on any particular location or locations. The first thing that comes to mind is the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on our activities, which changed the focus of the sessions. Lockdown explains the spike in sessions in my own back garden. Then in October 2022 the Firs was closed for removal of any remaining ash trees, for die-back mitigation, as the landowner was concerned that they might be found liable if anyone was injured by falling trees or branches. It hasn’t reopened to the public or for survey work since, as the contractors left it in a dangerous condition. Ravensroost Wood was also out of contention over winter of 2022 / 2023, due to more ash mitigation work, plus the 25 year coppicing becoming due, which required the use of specialist contractors, and there was too much activity and disturbance to make ringing sessions viable or safe during that period. This table shows the number of sessions by site by year:

Table 7: Number of sessions by location by year

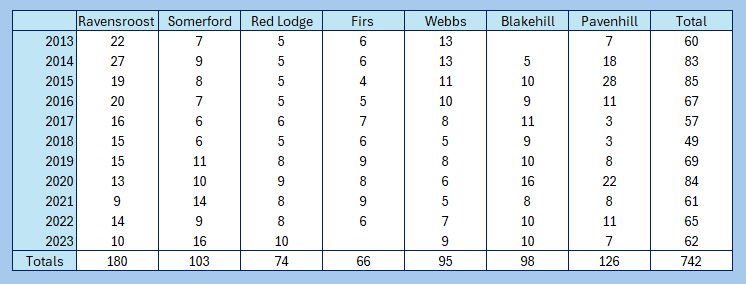

This table shows the breakdown of Blackbirds ringed by location by session by year:

Table 8: Blackbirds ringed by location by session by year

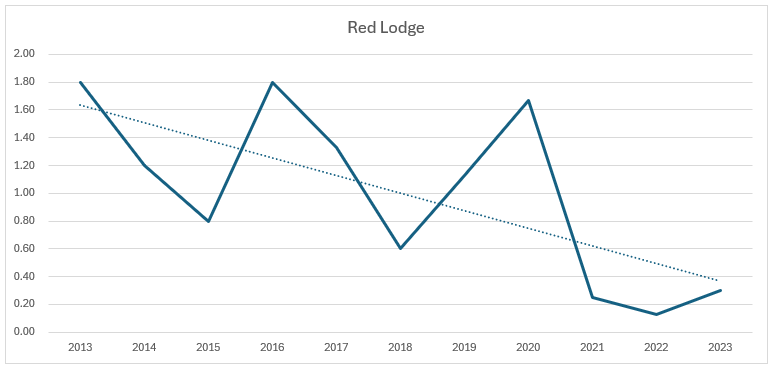

I have graphed these to identify the individual trends. As a single graph it was too busy to be clear, so I have created individual graphs for each site.

Graph 7: Blackbirds ringed in the Ravensroost complex by session by year

Graph 8: Blackbirds ringed at Somerford Common by session by year

Graph 9: Blackbirds ringed at Red Lodge by session by year

Graph 10: Blackbirds ringed in the Firs by session by year

Graph 11: Blackbirds ringed in Webb’s Wood by session by year

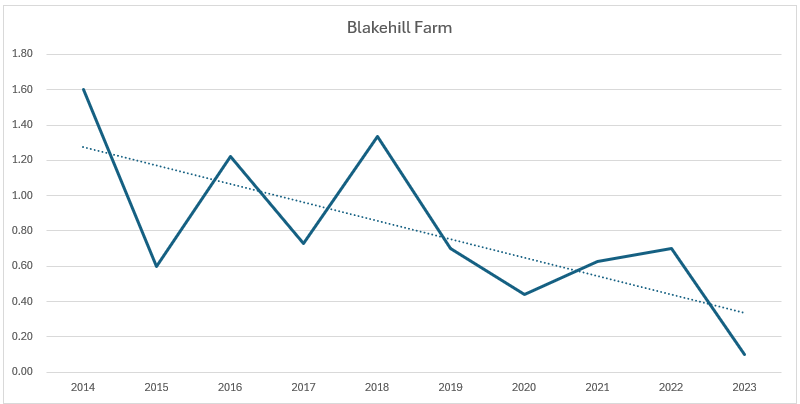

Graph 12: Blackbirds ringed at Blakehill Farm by session by year

Graph 13: Blackbirds ringed at Pavenhill, Purton by session by year

Every site is showing a reduction in the numbers ringed per session, with the exception of the Firs. That, alongside Pavenhill (my back garden), has the most volatile catching record. The following table shows the trends compared by site over the period of study:

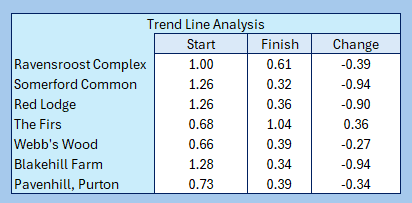

Table 9: Trend analysis and change in Blackbirds ringed by site

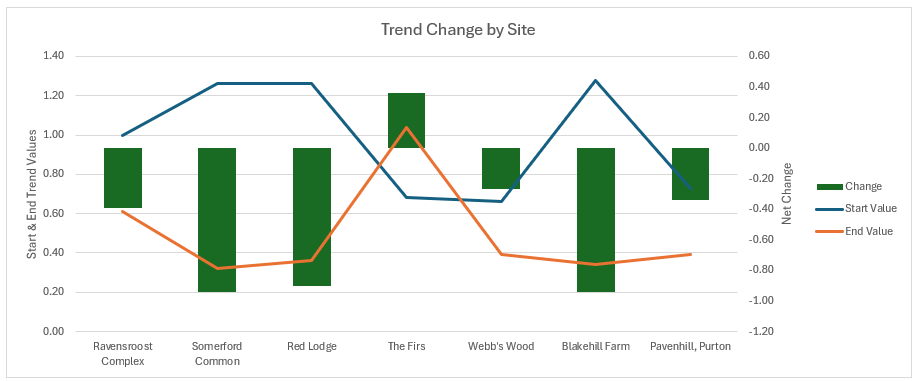

Looking at it in a graph gives a clearer picture of what the main affected sites have been:

Graph 14: Trend change by site in Blackbirds ringed over the period of study

What this clearly shows is that, although all bar one change has been negative, the biggest overall changes are the reduction in catches at Somerford Common, Red Lodge and Blakehill Farm. From my knowledge of the sites, it is hard to know what the drivers are. Blakehill Farm is managed as it always has been: a low intensity beef and sheep farm with extensive hay meadows, copses and hedgerows. Our ringing areas at both Red Lodge and Somerford Common have had some management activity: harvesting of Beech at Red Lodge, but that was over five years ago and the basic structure of the wood has not changed. Where we ring at Somerford Common has not undergone any major changes in the period covered by the study.

Clearly, the key factor in the overall decline has been the reduction in the catch over the last three years. There is no obvious reason why this should be the case. Worrying.