This post is somewhat different to my usual stuff. A little contentious, perhaps, but it shouldn’t be.

I graduated with a BSc (Hons) 2:1 in Zoology from Reading University in 1982. Unfortunately, with a wife and two children, and my then wife telling me that, if I went to Liverpool to carry out the PhD I had been offered, I would be doing so on my own, that was the end of my academic career. Instead, I spent the next 38 years working in IT, the last seven years of my working life being shared with professional wildlife survey work, alongside all of the voluntary stuff I was already doing. Much of my IT life was involved in software management, reporting and analytics: which is why I am now a bit of a data nerd.

Since I started bird ringing I have had plenty of opportunity to indulge my nerdiness, alongside my passion for wildlife. I have been lucky enough to have had a dozen or so articles published in the Wiltshire Ornithological Society’s WOS News, a couple in their science journal, Hobby, and a couple published in the Wiltshire Wildlife Trust magazine. Not claiming any sort of major academic achievement, just some stuff gleaned from my ringing data that other people found interesting. And, of course, I have been writing my blog since 2014.

As a student I was led to understand that science is about providing the best explanation of any phenomenon according to the best data available at the time. I read Karl Popper’s “The Logic of Scientific Discovery” and the contention that the true hallmark of a scientific theory is falsifiability. It still has pride of place on my bookshelves. To me that means that any hypothesis must be able to be tested to establish whether it is accurate or not. If it is, it adds to the sum of knowledge, whether positively or negatively. If it cannot be tested it is not science, in my opinion any such “hypothesis” claimed as truth is better defined as “faith” or “religion”.

When the first discussions about the negative impact of bird feeding started, they were all to do with the spread of disease. It was stated that the decline of some bird species was down to dirty feeders enabling infectious bacteria, viruses and parasites to be spread within populations. Testable, verifiable, falsifiable.

As a result, I hope that everybody has got the message that cleanliness is essential for the well-being of the birds using our feeders. Certainly, after catastrophic declines, the numbers of Greenfinch and Chaffinch in my garden have grown considerably over the last few years. That is supported both by observational data provided to the BTO Garden Birdwatch Scheme and my ringing data. My feeders have always been kept clean and regularly disinfected and rested between refills. Given the increases, it looks as though the message has got through to the neighbours as well. Mind, there is still the unanswered question of why some species have clearly experienced reductions in numbers but some have expanded their numbers, despite the expansion being in the most regular users of bird feeders and, therefore, more exposed to the potential for contracting disease. I am thinking particularly of Blue Tit, Great Tit and Goldfinch.

More recently a proposition has been put that bird feeding is enabling certain prolific species to out-compete other less prolific or aggressive species and, taking it to an extreme, helping to drive the extinction of the Marsh Tit and Willow Tit, and that we should stop feeding the birds in our garden. Certainly, if we stop feeding birds in our gardens we will see far fewer birds. Whether it would translate into population declines I have no idea. The idea that feeding birds in your garden is adding to the competitive pressure on species that don’t take advantage of it is, in my opinion, an hypothesis, but one that is virtually untestable. One would have to persuade a huge number of people to stop feeding birds in their garden for years to establish the population impacts. That is not going to happen.

I could suggest an alternative proposition: that by Blue and Great Tits taking advantage of easy food available in our gardens they are leaving more of the wild natural food for those species that don’t take advantage. Far from having a negative effect, it could be a positive. Why is that any less viable than their hypothesis?

Those promoting this idea do not make definitive claims, but it is often referred to as if it is fact, hidden behind “could” and “might”, et cetera, as a cover for it being an untested hypothesis. I have found no evidence, let alone any peer-reviewed science, to back up their “theory”. In science, instead of it being “acting on faith”, it becomes “acting on the precautionary principle”, i.e. we can’t test it, can’t prove it, but we would like others to believe it and act accordingly. That is surely what religion is based upon?

I first became aware of the suggestion in October of 2021, when I read a paper, published by Shutt et al, on the movements of Blue Tits. Their movements were monitored by the provision of peanuts that had their DNA bar-coded, and the recovery of faecal samples from nest boxes at known distances from the food sources for DNA analysis. The ideas in this article interested me, so I had a look at the Blue Tits and their movements in my main ringing area, the Braydon Forest, based on my ringing recoveries. What I found was that I could not replicate their findings of significant numbers of movements with my ringing data. You can find references to titmice movements in some of my other blog posts. I will provide an updated analysis of movements in a future post. Needless to say, with some 10 years worth of ringing data to analyse, I was pretty confident in what I found. As I said at the time: “Of those 1,523 recaptures only 4 of them were ringed in my garden and recovered elsewhere, and only 2 of the 3,430 birds ringed elsewhere have been recaptured in my garden.” This was data up to the time that I wrote my October blog piece in response: “Feeding Blue Tits in Your Garden: a Good or a Bad Thing”.

https://braydonforestringing.uk/2021/10/19/feeding-blue-tits-in-your-garden-a-good-or-a-bad-thing/

Throughout my original piece I reiterated that I was not querying their results, just saying that I could not replicate them. The one thing that I did say, though, was that they had not allowed for the impact of providing the nest boxes they needed to be able to collect their samples. Also, they did not differentiate in their paper how many times individual birds returned to the feeders and where they subsequently flew off to, i.e. were birds exploiting one food source multiple times, using them as a central feeding station, and then flying distances to the same box or different, or were they individuals “just passing through”, or a mixture of both. This is something that ringing data and / or PIT tags can give you. The Edward Gray Institute in Oxford have studied Blue Tit movements and feeding site frequency in their sites for many years using those techniques.

Although the Shutt study states that they carried out the study under a BTO ringing licence, there is no reference in their work to individual birds, frequency of capture, etc that I can find. If I have overlooked it, and I have read it more than once, I am happy to be pointed in the right direction. The analysis of my data was all based on individually identifiable birds and continues to be so.

Then, in January 2022 the following article appeared in British Birds: “Rethinking bird feeding” by Richard Broughton, Alex Lees and Jack Shutt (of the previously mentioned paper). They are part of a cohort of academics that I think are agitating for the reduction / end of supplementary feeding of birds in both gardens and woodlands. I hope I haven’t misrepresented their position and am happy to be corrected if I have, or if it is more nuanced than that. In the article they suggested that feeding the likes of Blue Tits, Great Tits and Great Spotted Woodpeckers in your garden was increasing their populations, which was helping to drive the extinction of Willow Tits and Marsh Tits in the UK. This was my first full exposure to this untested, almost certainly untestable, hypothesis. It was touched upon in the Shutt paper, but this was a much more definitive assertion. To illustrate the inter-specific competition, they put a photograph up captioned “Marsh Tit chased from a bird table by a Blue Tit”. It shows no such thing: it shows a Marsh Tit feeding on seed scattered on a tree stump used as a bird table and a Blue Tit on the opposite side of the stump but not actually on the feeding area. The Marsh Tit is paying no attention to the Blue Tit, just feeding. Perhaps if they had waited a few seconds they might have got what they wanted but, having watched Marsh Tits and Blue Tits sharing both peanut and seed feeders, I think the authors were seeing what they wanted to see. Given that it was the Marsh Tit stood there feeding, one could actually reverse the caption. You will have to look it up: I am not sure of the copyright rules.

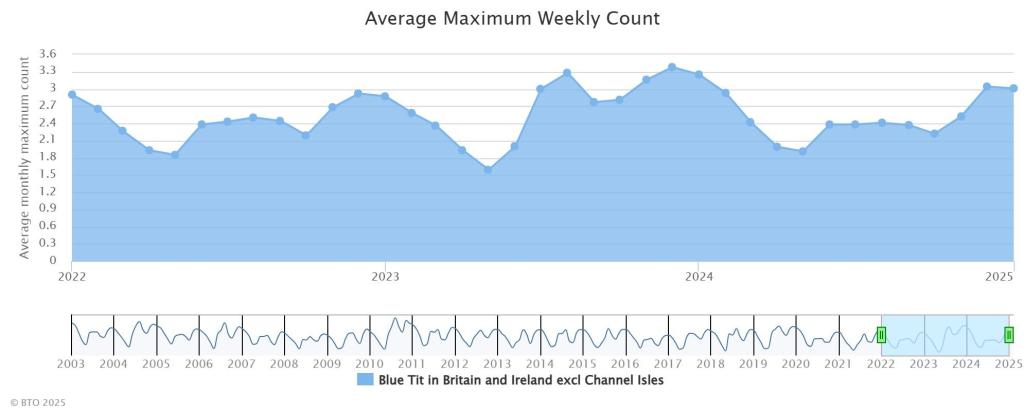

One thing that would be important in their hypothesis would be significant increases in the numbers and frequency of those species using gardens. I have had a look at the BTO Garden Birdwatch (GBW) figures for Blue Tit garden usage and reproduce their images, graphed from millions of records, below:

In this graph we are looking at maximum weekly counts of between one-and-a-half and three-and-a-half Blue Tits visiting each garden in which they are recorded. I know from my ringing data that it is an under estimate, but it is relatively consistent. In 98 sessions in my garden when we caught Blue Tits, the average catch is 4.4 per session. That said, I do catch them far less often than I see them in my Garden Birdwatch counts. Since I got my C-permit, 11 full years have elapsed: i.e. 572 sessions, less 30 weeks for when we have been away on holiday. Garden ringing sessions in the same period is 178, and I have caught Blue Tits on only 98 of those occasions.

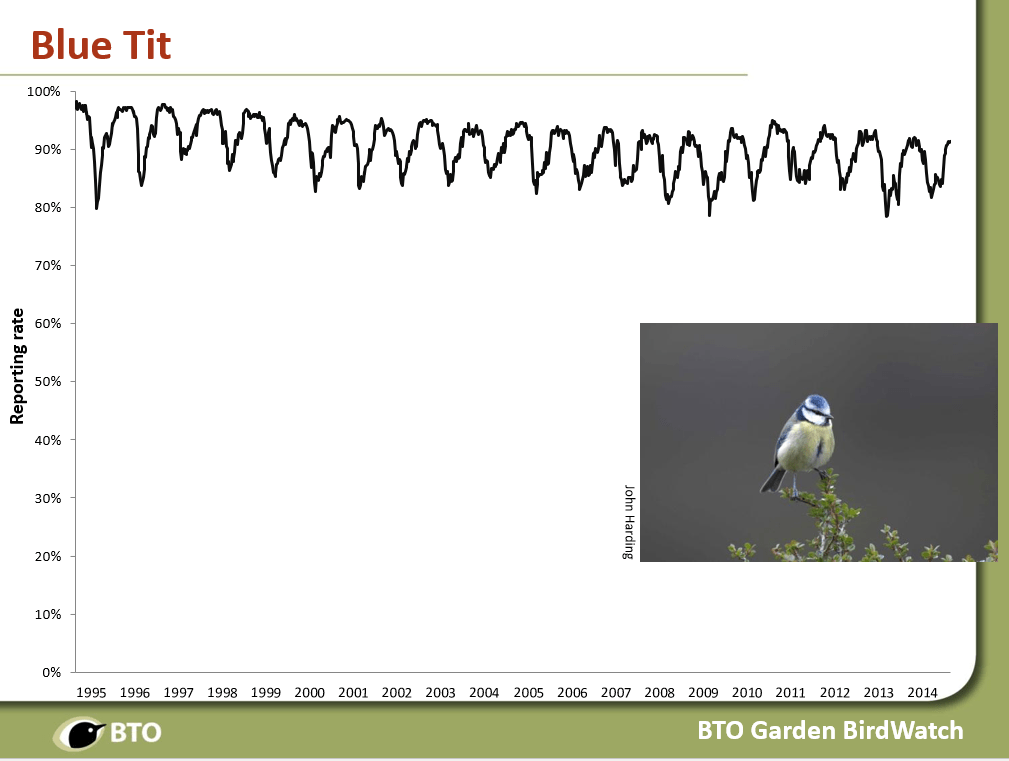

To me, the graph shows the last three years are up and down, but the bottom image showing 24 years of data shows no obvious growth in the numbers of Blue Tits using our gardens. In fact, during my time as a BTO Garden Birdwatch Ambassador I was given a number of PowerPoint slides to use to illustrate talks, including this one on the frequency of Blue Tit recorded in gardens between 1995 and 2014:

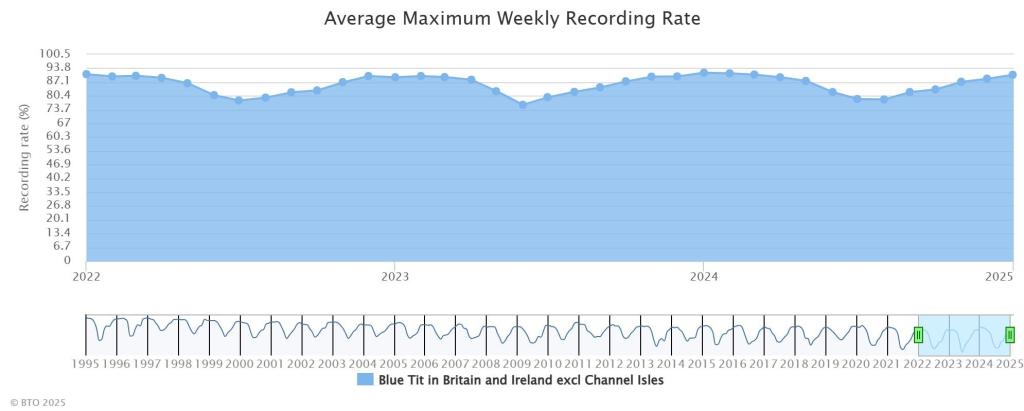

As you can see, the usage is high, but the trend in that data is very definitely downwards, i.e. a reduction in usage of our gardens by Blue Tits. Ironically, if there is a small peak, it is in the three years following their article. If you look at the most up to date reporting rate of Blue Tits in the garden, the trend is very definitely downward, using the data at the bottom of the image spanning 1995 to the end of 2024:

The trend shown by GBW data for Great Tits is that, over the same period, their usage and maximum observed counts are stable but lower than the figures for Blue Tits. Essentially, the increase in garden feeding of these species is not supported by the evidence.

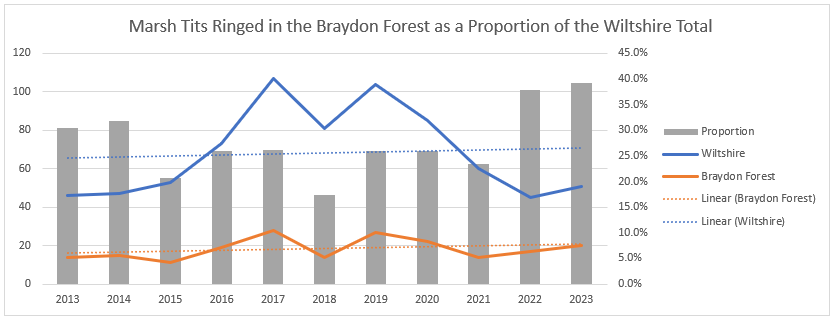

When someone raised the issues from the British Birds article on Twitter, and said that, as a result, he would cease feeding birds in his garden, I joined the conversation, using the data from my ringing activities and my previous blog post. They show that our local Blue and Great Tit populations have been stable, with slight declines, since I started my Braydon Forest project in late 2012. It also shows that our Marsh Tit population is absolutely stable, increasing slightly and slowly. Cue a few very negative responses from the academics, one was quite angry, despite the fact that all I was doing was reporting on the data from my own area, and stressed that I wasn’t querying anyone else’s results. The most unfortunate outcome though was that, because my data didn’t fit the hypothesis, Dr Broughton claimed that the population of Marsh Tit in the Braydon Forest was insignificant. Personally I think that all data is important.

What prompted this post was that last week a friend messaged me to ask about the impact of supplementary feeding, having seen Richard Broughton’s author interview with NHBS about his new Poyser book on Marsh and Willow Tits. In that interview he said:

“It’s also important to realise how we can unintentionally make things harder for Marsh Tits and Willow Tits when we do favours for their competitors. There is growing evidence that increasing numbers of Blue Tits and Great Tits could be harming Marsh Tits and Willow Tits by taking over their nests and dominating their foraging space. The vast scale of bird-feeding in gardens, woodlands and nature reserves is changing our woodland bird communities, and it really boosts the dominant species, which can then put extra pressure on Marsh Tits and Willow Tits. For this reason, it’s important to consider the unintended negative impacts of well-meaning interventions, such as bird-feeding and nestboxes, on more vulnerable species like these.

This is the link to the full piece:

https://www.nhbs.com/blog/author-interview-with-richard-broughton-the-marsh-tit-and-the-willow-tit

My concern regarding the piece is the repetition, quietly though it is made, that feeding birds in your garden is detrimental to other species. He says there is evidence: where is the evidence? I have written previously about the fallacy of Correlation = Causation. It should be anathema to science.

As the GBW charts show, there hasn’t been a massive increase in the utilisation of gardens by Blue Tits in the last 30 years, yet the Marsh Tit numbers have continued to decline. In my opinion, the difference between my Braydon Forest sites and many others is the absence of nesting boxes for titmice. There have been no new titmouse boxes installed in any of the five sites in over 20 years. One or two wrecked old boxes can be seen in Ravensroost Wood, but the only boxes erected within the wood have been some bat boxes and a few open-fronted boxes for Spotted Flycatcher. The only other wood with any number of nest boxes was Webb’s Wood. These were Dormouse boxes, with the entrance adjacent to the tree trunk, but these have been removed now. Observers did find the odd Blue Tit roosting in them, but not many. The thing is that this is a testable hypothesis: that the provision of titmouse nest boxes is leading to local increases of Blue Tits. The Braydon Forest could be a nice control area for the hypothesis. How you would then tie that directly to the decline of Marsh Tits is a different question.

Having had the population of Marsh Tits in the Braydon Forest described as “insignificant” prompted me to have a look at the data to see just how insignificant it is. I have looked at the years 2013 to 2023 inclusive. 2013 was the first full year that I had data for the five sites I survey in the Braydon Forest (Firs Wood, Ravensroost Wood, Red Lodge, Somerford Common and Webb’s Wood) and 2023 is the most recently published ringing totals from the BTO. When I compare the numbers ringed for the Braydon Forest against the numbers ringed across the whole of Wiltshire, I get the following:

When I graph that up:

The trend lines are positive for both the entirety of Wiltshire and the Braydon Forest. It could be argued that the 2017 and 2019 spikes distort the picture, but those spikes are much less prominent within the Forest and 2018 was a significantly poor year. If I remove those three years from the chart the trend line is even more positive for Marsh Tits in the Braydon Forest.

Just for fun, I had a look at what proportion of the entire woodland of Wiltshire is covered by my five sites:

So, 26.7% of the Marsh Tits ringed in Wiltshire comes from just 0.86% of the available woodlands! Now, obviously, I am being facetious: not every woodland is covered by the ringing scheme and not every woodland is suitable for Marsh Tits. That said, at least 50% of Somerford Common is unsuitable for Marsh Tit, being conifer plantation, and I only cover about 25% of Ravensroost Wood, 10% of Red Lodge, 20% of Somerford Common and 10% of Webb’s Wood. If I take that into account, then 0.15% of the Wiltshire woodland produces 26.7% of all Marsh Tits ringed.

Thanks in part to my feedback to Forestry England, they have made the Marsh Tit their priority bird species for the Braydon Forest, and recently thinned out a huge amount of the beech, and removed much of the non-native conifers, from Webb’s Wood, and the catch of Marsh Tit, along with several other species, has improved as new understorey has generated and, quite possibly, improved feeding options.

I am not claiming that we have a huge population: I ring on average 20 new birds and process 35 individual birds per year in the five main woodlands I work in the Forest. I do claim that, in ringing terms, it is a significant Wiltshire population, especially when you consider the other woodlands it is up against: the northern parts of the New Forest and Savernake Forest and its surrounding woodlands. Savernake Forest alone, at 1,821 hectares, could swallow the Braydon Forest almost five times over! I know for a fact that bird ringing takes place in these sites, plus many more woodland sites in the north of the county, particularly around Swindon east and south, Devizes and Trowbridge.

My data shows that the Marsh Tit population is stable, that populations of Blue and Great Tits show a slight decline and Coal Tits are the ones to worry about.

I am certain that the decline of the Marsh Tit is primarily down to woodland fragmentation and management, rather as outlined in Dr Broughton’s DPhil submission referenced below. It is highly likely that nest box provision is an exacerbating factor. It is a well known fact that Marsh Tits are highly sedentary: with less than 5% of them moving more than 1km from where they were hatched, so fragmentation and deforestation will clearly have a significant impact. The five woodlands that I catch Marsh Tits in are relatively close to each other: the longest distance between my ringing sites is between Red Lodge and Somerford Common West, at 3.8km. The shortest distance is between Webb’s Wood and the Firs, at 568m. Of the 220 Marsh Tits ringed between 1st January 2013 and 31st December 2024, 121 have been retrapped at least once. Of those, only two have been caught more than 1km from where they were ringed. D983277 was ringed in Webb’s Wood on the 13th June 2014 and recovered in Red Lodge on the 24th January 2016: a distance of 3.16km. This looked like a juvenile dispersal. The other was AAL0191, ringed on 21st January 2020, and recovered in Somerford Common on the 22nd November 2023: a distance of 2.1km. More interestingly, this bird was retrapped in the Firs on the 9th October 2023 before being recovered at Somerford Common. In between, significant forestry works started in the Firs, removing all of the Ash and a large quantity of Oak (as part payment for the Ash removal) and I wonder if it moved because of the disruption.

If anybody can provide me with a link to a project, and subsequent peer-reviewed papers, which show a genuine link between feeding birds in your garden and the decline of the Marsh Tit, I will change my opinion and bird feeding behaviour, because that’s what you do when new testable, replicable data comes along!

References:

Robinson, R.A., Leech, E.I. & Clark, J.A. (2024) The Online Demography Report: bird ringing and nest recording in Britain & Ireland in 2023. BTO, Thetford (http://www.bto.org/ringing-report, created on 17-October-2024)

Broughton R.K.; Shutt J.D. & Lees A.C.: Rethinking bird-feeding

British Birds, vol. 115, pp 2 – 5

Shutt et al: 2021 faecal metabarcoding reveals pervasive long distance impacts of garden bird feeding:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.2021.0480

Broughton R.K.: 2012 Habitat Modelling and the Ecology of the

Marsh Tit (Poecile palustris) DPhil thesis submission to the University of Bournemouth

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the BTO Garden Birdwatch Scheme for producing such good graphical analysis of their data.