After posting the link to the piece onto BlueSky, I was having a browse and found a repost by Alex Lees. It was a video showing a Chaffinch floundering around in a garden, under some feeders, with its legs missing, due to Fringilla papillomavirus. This disease, of course, he attributed to being spread at feeding stations. Firstly, Fringilla papillomavirus was first discovered in Chaffinch populations of the UK in the 1960’s, long before the exponential boom in garden bird feeding. Secondly, it is widespread across the world and across species, despite the fact that garden bird feeding is much less prevalent outside of the UK, although garden feeding is certainly increasing in western Europe.

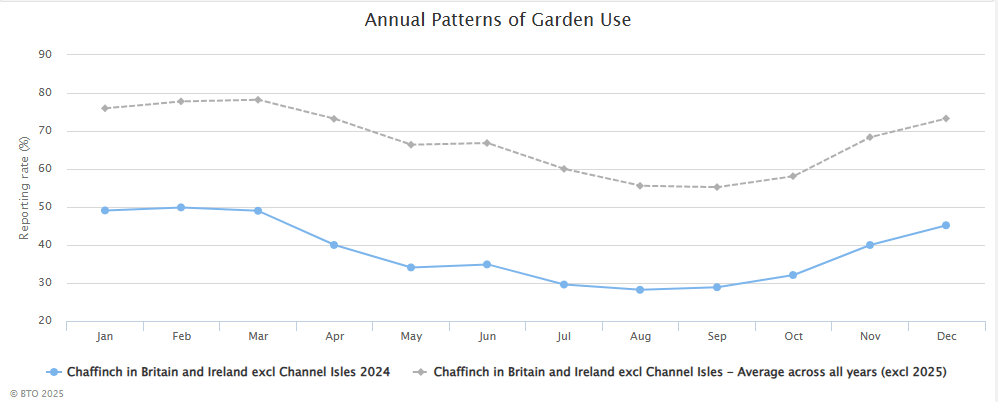

I find this hard to understand. Chaffinches are not particularly prolific users of gardens, according to the data from the BTO’s Garden Birdwatch scheme, my own GBW observations and my own ringing activities. Also, the disease is widespread across Europe and beyond: in those countries where bird-feeding is not as concentrated as it is in the UK. Yet they still have Chaffinch suffering from the disease.

Not every scientific group is as desperate to blame its spread on garden bird feeding as those in the UK. This paper, for example:

It is open access and good reading, with some extremely graphic photographs. The last phrase of their paper states: “The mode of transmission, current prevalence of papillomavirus infections in chaffinches, bramblings, and other wild bird species, and effects of the infection on the fitness of the affected subpopulations are unknown and deserve continuing attention.”.

From a variety of other sources I have learned that Papillomaviruses infect a number of other species: Chaffinch, Greenfinch, Canary, Brambling, Northern Fulmar, African Grey Parrot, Yellow-throated Francolin, Mallard and Adélie Penguin. I don’t remember seeing too many of the last five at my feeding stations!

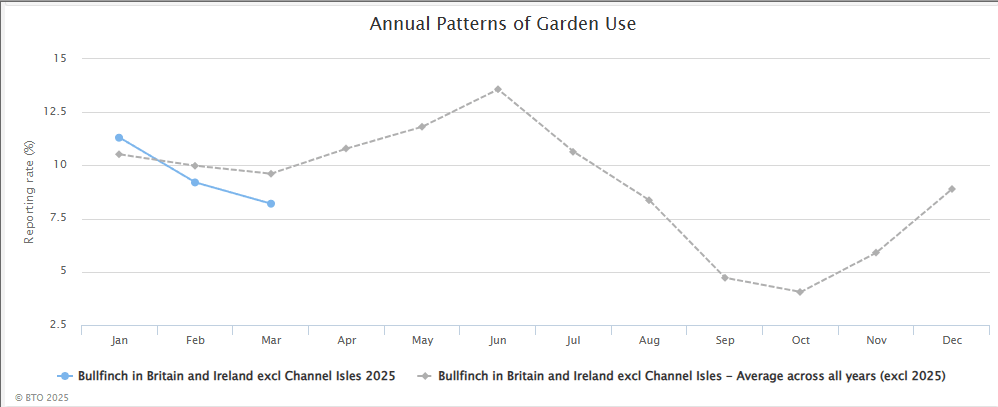

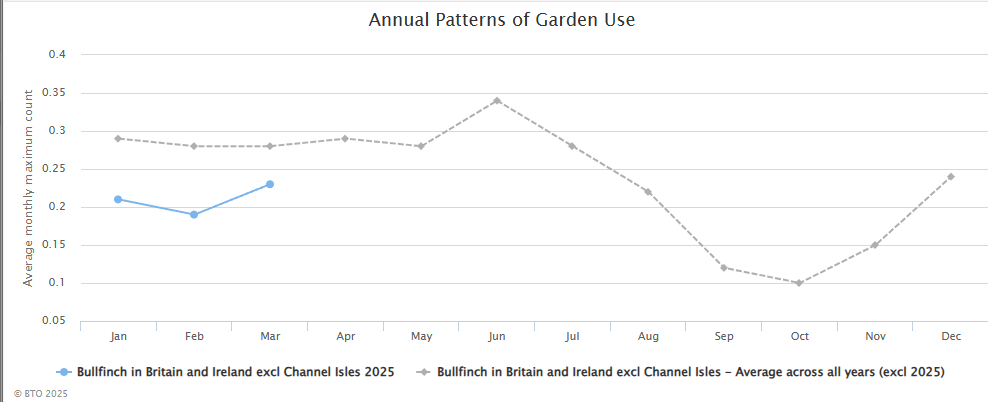

These graphs have been taken from the BTO’s Garden Birdwatch data: hundreds of thousands of records from thousands of observers and, even at the heights of their population maximum counts were between two and four in each garden. Since the population crash (I will discuss Trichomoniasis in a separate post) you can see the numbers and frequency have halved, making close interactions and, therefore, virus transmission somewhat less likely.

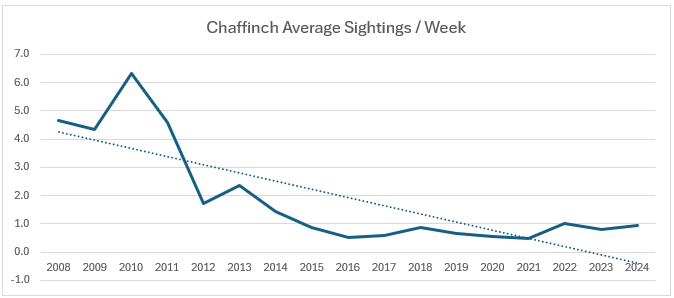

When I look at the number of Chaffinch that I have ringed in my garden, it averages out at three per year. However, when I look at the sightings that I have reported to the Garden Birdwatch Scheme, I get the following graph:

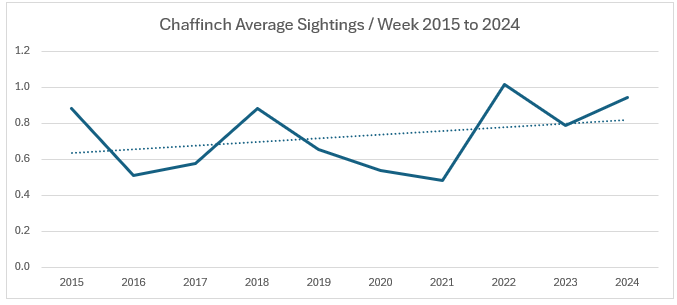

As you can see, there was a huge drop off after 2010. Presumably the results of Trichomoniasis. Such a steep decline, which rather distorts the reality of how it is today. However, the highest weekly average was 6.3 in 2010 and the lowest was 2016, 2020 and 2021. If I graph the data from 2015 onwards it shows a rather different story:

The highest is 1.0, in 2022. I can honestly say that I have not seen a Chaffinch with FPV in my garden for at least five years. However, away from the garden, in my Braydon Forest sites, I would estimate that one in five Chaffinch we catch has to be released because it has either developed FPV or shows signs that it might be: usually, the legs are showing some sort of greenish colouration. This is not to be confused with the white socks of a Cnemidocoptes mite infection. We did have a Chaffinch with the mite infection visit the garden between 2021 and 2023, but I haven’t seen it for a long while. Of course, as soon as I saw it in the garden I would disinfect the feeder it had accessed. That said, I am not sure how much it could have spread that disease at my feeding station as I have never seen any sign of it in any other Chaffinches: either in my garden or at my ringing sites.

Alex describes his position:

I’m here for the evidence. Increased competition may be a significant factor in Marsh Tit declines. Increased competition and predation is likely the most significant factor in Willow Tit declines. Diseases mostly spread at feeding stations underpin declines in Chaffinches and Greenfinches.

Where is the evidence? There is zero evidence for that last sentence: this is his belief, his faith, his religion. I suggested an alternative. How are viruses spread? The Human papillomavirus is spread through intimate contact, i.e. it is contagious. How is influenza spread? Through exhalation of infected droplets. How likely are Chaffinches to come into those sorts of direct contact with their conspecifics at feeding stations if the maximum number recorded at any one time is four across all year’s data, but fewer than two at any one time in the last year?

This quotation from the Lawson, Robinson et al paper cited below:

“However, it is not possible with the available data to evaluate the relative importance of risk factors for occurrence of finch leg lesions, and the extent to which supplementary feeding may alter their occurrence.”

It is worth reading: they do suggest the possibility of transmission at feeding stations but, significantly, they do not put the emphasis on it in the same way that the anti-feeding cohort continue to do.

I suggested an alternative: in Wiltshire ringing activities find large flocks of Chaffinch on farmland in the winter. They take advantage of game cover, winter stubbles, etc. Bearing in mind that one never gets to ring 100% of what is there, when you are getting catches that can be in excess of 60 individuals in one session, it shows that they are large flocks. Large flocks that roost together, large flocks that will huddle together for warmth. According to Dr Lees “Roosts don’t provide as suitable conditions for transmission for either disease nor in fact same pairwise opportunities for transfer as on/below feeders given substrates.” My answer would be “why not?”. I am pretty sure that if you took a large group of humans, several of whom are suffering from influenza, and put them in close proximity for eight or so hours, huddling together to keep warm, there would be several uninfected members of that group that would become infected.

Mentioned in the first two papers cited below is the incidence of FPV in Bullfinch. Anecdotally, when out ringing we find a similar proportion of Bullfinch with FPV to that which we find in Chaffinch. I find it interesting for two reasons: the extremely low frequency of Bullfinch visiting garden feeding stations and the small numbers that visit gardens:

I have only ever ringed a single Bullfinch in my garden and the averages recorded under GBW are negligible: since 2008 I have only recorded Bullfinch in 8 years, the rest have had an average of two per annum, and I haven’t recorded any since one in 2018.

For the absence of doubt: I do not deny that garden feeding stations can be a terrible source of disease for birds. Infections caused by Salmonella, E.coli and Suttonella (hadn’t heard of that until I started looking into this) are clearly easily spread from dirty bird feeders. For that reason, I scrapped the bird tables from my garden, I use hanging feeders, clean and disinfect them regularly, swap them out and rest them in between fills. I do not want to be responsible for spreading disease within our local bird populations.

Citations:

Lawson, B., Robinson, R.A., Fernandez, J.RR. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics and aetiology of proliferative leg skin lesions in wild British finches. Sci Rep 8, 14670 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32255-y

Hugh J. Hanmer, Andrew A. Cunningham, Shinto K. John, Shaheed K. Magregor, RobertA. Robinson, Katharina Seilern‑Moy, Gavin M. Siriwardena1 & Becki Lawson: Habitat‑use infuences severe disease‑mediated population declines in two of the most common garden bird species in Great Britain. Nature Scientific Reports | (2022) 12:15055 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18880-8

I. Literak; B. Smid; L. Valicek: Papillomatosis in chaffinches (Fringilla coelebs)

in the Czech Republic and Germany. Vet. Med. – Czech, 48, 2003 (6): 169–173