This will be the final chapter on this topic – unless someone else decides to go all zealous over something that is not necessarily supported by the data available, closing off other avenues of investigation. I intend to cover off the situation regarding that horrible disease Trichomonosis.

From personal anecdote, I know that when I moved to north Wiltshire in 1997 I could find flocks of 30 or so Greenfinch coming to my garden. Back in those days I had a bird table as well as hanging feeders. Everything was always cleaned and disinfected on a regular basis but, of course, wood has places for bacteria, viruses and parasites to hide and possibly avoid the disinfectants. I ditched the bird table two decades ago. Regardless of my precautions, I would occasionally see a Greenfinch showing signs of Trichomonosis. No more than one a year, and I would take down the feeders, clean, disinfect and leave down for a week. I have no idea where they caught it from, but you notice them when they come to your garden, which perhaps explains why so many are prepared to conflate the two: correlation = causation, the bane of science!

I have not seen any sign of any bird with Trichomonosis in my garden for nigh on a decade. These days, the local population has shown good signs of recovery. This year I regularly have four or five pairs visiting the feeders in my garden and I have heard at least three singing males within earshot of the garden. My largest recent sighting in my garden was 25 individuals, in the first week of February this year.

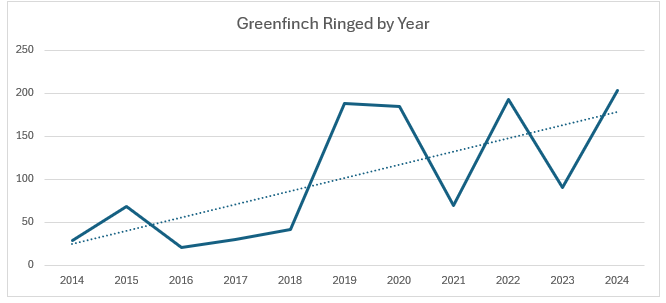

Whilst our group ringing results are very much of the yo-yo variety, there is a distinctly upward trend (which would be better if I ringed in my garden more frequently than I have done recently):

There is no doubt: there was a massive outbreak of Trichomonosis in the west country of the UK in 2005, primarily affecting Greenfinch and Chaffinch (as if Chaffinch didn’t have enough to cope with, with Fringilla papillomavirus as well). However, the parasite had been in the UK for centuries in the bird world, endemic in pigeons and doves. Was this the source of transfer to the finches? If so, what was the mechanism?

It is almost certainly spread within species by infected individuals where both courtship feeding and feeding their young involves regurgitating food: an excellent method of passing the Protistan, Trichomonas gallinae, from the host to a previously uninfected other. It also passed into various birds of prey, noticeably Sparrowhawk and, no doubt, if illegal persecution stops, it will be found in UK Goshawks – because it is, and is long established as such, in European populations. Some of the Sparrowhawk and Goshawk’s favourite prey, particularly female Sparrowhawks, are pigeons and doves, so it is not hard to understand how that transference might have happened. That is something that has been seen the world over, as evidenced by the paper referenced below by de Chapa et al. What is not so clear is exactly how it transferred into Greenfinch and Chaffinch, presumably from pigeons and doves, but, seemingly, not into other species common at bird feeding stations, if bird feeding is the source.

Something else that I find distinctly odd: Goldfinch. They are unarguably the commonest finch found at UK garden feeders these days. I have not seen any reports of UK Goldfinch showing signs of Trichomonosis, certainly not seen any sign in my garden, and they have undoubtedly increased their population significantly since 2005! I have ringed just under twice as many in my garden as I have the next commonest species (Blue Tit, unsurprisingly). However, studies in France have found that the parasite is spreading through their population over there. (Chavatte et al., 2019). The latest RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch results showed that they had gone up one place in their top 10 observations. Why aren’t we seeing the French situation impacting Goldfinch in the UK?

One issue that I have with the story of the spread of Trichomonosis is that, if the anti-bird feeding cohort are to be believed, the UK is not only responsible for it spreading throughout our susceptible birdlife, primarily Greenfinch and Chaffinch, but, apparently, responsible for spreading it to all of the birds that have now caught it in Europe! The bird feeding “boom” in the UK happened in the 1980’s. I would be relatively certain that this was, in part, due to the introduction of the RSPB’s Big Garden Birdwatch in 1979, encouraging people to take more notice of and engage more with, the birdlife in their gardens.

I am not blaming the RSPB for this being the cause of the spread of Trichomonosis. To start with, why did it take 25 years to cross the species boundary, given the lack of awareness about cleanliness, and the spread of various diseases, like Salmonellosis, in the public consciousness, until the early 2000’s?

The Trichomonas parasite, according to the British Veterinary Association, can survive outside of the host, in dry conditions, for a minute or two at most. In damp or wet conditions for two to four minutes. Just think on the likelihood of any individual bird picking up that parasite in that time window from a hanging feeder? Ask the question, given that Blue Tit and Great Tit are so common at feeders, why hasn’t Trichomonosis been found in those species? Or is it there but they are resistant to the parasite? Has anyone looked?

Recently, Dr Alex Lees promoted a paper on Twitter from 2015 which investigated the length of time the parasite can live outside of the host in four different water treatments. They found that, under suitable conditions, the parasite can survive for much longer periods in different wet conditions. Fair enough, however, I have read that paper by Purple et al, referenced below. Their treatments are sensible: but their work was all done under laboratory conditions. They took water samples from real life situations. Then they took their four water types and sterilised them before inoculating them with significant quantities of T. gallinae. These cultures were then kept at a steady 23oC and samples taken at 0, 15, 30 and 60 minutes. Those samples were transferred to a suitable nutrient medium and incubated at 37oC, and then assessed for the presence of motile Trichomonas parasites in the sample. They considered that discovering a single motile Trichomonad was evidence of persistence. Let me put this into context: the 500ml samples that they initially incubated were inoculated with approximately one million individual Trichomonads! What is the likelihood of a single Trichomonad, surviving in one litre of water in a bird bath, being in a position to infect a Greenfinch that just happened, unfortunately, to stop off for a drink at just the wrong time? What is the likelihood of there being a million Trichomonads in anyone’s bird bath? How “real” are the experimental parameters? How many bird baths sustain a temperature of 37oC? Surely the timing should have been done on media kept at the same temperature as the original water samples?

Has anybody done random sampling of bird baths and other water sources under natural conditions and tested for T. gallinae? You can find plenty of warnings about cleanliness being next to godliness, and papers on other diseases unequivocally helped to spread through poor hygiene, but it seems that nobody has actually done the work to see how widespread Trichomonas is in UK bird baths or ponds, or any other water source. If you know better, please point me in the right direction. I have searched for suitable references but been unable to find any, and I would love to read the evidence that renders this post redundant!

A key issue for me, though, is the speed with which the disease has reputedly spread. After such a slow start, 20+ years after the bird feeding boom, until exploding from the West Country in 2005, to being found in Fenno-Scandia in 2008, then Germany and Czechia in 2009. If the UK is to blame, that is an incredibly fast spread for a disease which is not a viral or bacterial infection / contagion. Reputedly, these countries do not have the same density of bird feeding as we do in the UK, so what is behind the spread there? Obviously, birds can fly and migration can spread disease – if they are well enough to make the journey. Most birds I have seen suffering from Trichomonas can barely flutter out of the garden, let alone cross the North Sea!

According to Jim Flegg in his book “Time to Fly”, looking at migration based on ringing data, the Greenfinch is “largely sedentary, with some occasional partial migrants”. Only, as he explains, the migration that does occur is from areas of Fenno-Scandia, but to the east and north-east of the UK. So, this disease had to spread right across the UK to those eastern counties, to infect the Fenno-Scandinavian and central European Greenfinches overwintering in the UK, to then take the disease back to their countries of origin, all within that three year timeframe!

As a newly qualified C-permit holder, I went and spent a long weekend at Gibraltar Point Observatory in 2014. In one session we caught some 30+ Greenfinch and the staff were adamant that they still had a very healthy population of them in Lincolnshire and that they had not seen any particular fall off. I would be interested to see a time-stamped geographical representation of the spread of the disease within the Greenfinch population. As part of my presentations, when I was a BTO Garden Birdwatch Ambassador, I was provided with a set of PowerPoint slides showing the spread of Avian Pox in the Great Tit population. It spread out from the south-east of England to affect birds across the north and west of England in just three years: from 2008 until 2010. The data came from work by Lawson et al, referenced below. That is not too surprising: it is a virus spread by mosquito. Mosquitoes, as everybody knows, can be extremely effective vectors of disease. Both Malaria and Sleeping Sickness are infections spread by mosquitoes, caused by parasitic Protozoans: Plasmodium spp. and Trypanosoma spp. respectively. Has this been considered for the spread of Trichomonosis, or, having decided on what to blame, has nobody looked at the possibility?

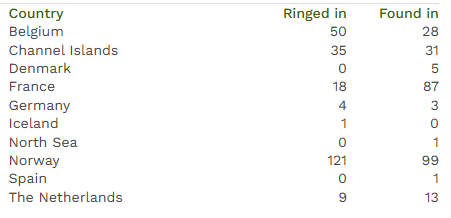

The BTO’s ringing recovery data is interesting, in all of the decades that recoveries have been recorded, these are the total numbers of Greenfinch recovered and reported, either ringed in the UK and recovered in other countries and vice versa:

These hardly represent mass movements.

Parasites of the genus Trichomonas are widespread: with many species infecting a wide variety of animals in different ways, including the human animal. In humans it is a sexually transmitted infection. I am not disputing the impact on Greenfinch and Chaffinch but, by going for the easy target, it is entirely possible that other routes of infection are being overlooked and not addressed.

I will repeat: if there is unequivocal evidence, I would love to see it and read it. Not being a zealot: I am open to changing my opinion, based upon new and contradictory evidence.

This is an opinion piece, not a scientific dissertation, so I have listed just the key references that I have used in putting this together. I have read quite a few more.

References:

Kathryn E. Purple, Jacob M. Humm, R. Brian Kirby, Christina G. Saidak, Richard Gerhold: Trichomonas gallinae Persistence in Four Water Treatments; Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 51(3), 2015, pp. 739–742; Wildlife Disease Association 2015

Flegg, J. Time to Fly: Exploring Bird Migration, British Trust for Ornithology, 2004

Manuela Merling de Chapa, Susanne Auls, Norbert Kenntner, Oliver Krone: To get sick or not to get sick—Trichomonas infections in two Accipiter species from Germany; Parasitology Research (2021) 120:3555–3567

Jean-Marc Chavatte, Philippe Giraud, Delphine Esperet, Grégory Place, François Cavalier, Irène Landau: An outbreak of Trichomonosis in European greenfinches Chloris chloris and European goldfinches Carduelis carduelis wintering in Northern France; Parasite 26, 21 (2019); https://www.parasite-journal.org/articles/parasite/full_html/2019/01/parasite180155/parasite180155.html

Lawson B, Lachish S, Colvile KM, Durrant C, Peck KM, et al. (2012) Emergence of a Novel Avian Pox Disease in British Tit Species. PLOS ONE 7(11): e40176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040176

Robinson, R.A., Leech, D.I. & Clark, J.A. (2024) The Online Demography Report: Bird ringing and nest recording in Britain & Ireland in 2023. BTO, Thetford (http://www.bto.org/ringing-report, created on 4-September-2024)