I cannot wait until I get access to the 2025 Blue Tit ringing results for England and Wiltshire in 2025, as the basic data for the West Wilts Ringing Group is looking pretty good and the part the Braydon Forest has played in that is everything I wanted.

One of the arguments advanced by the anti-feeding academics is that feeding Blue Tits is helping drive the extinction of Marsh and Willow Tits (British Birds, January 2022). My argument is that they have two conflicting positions: one is that supplementary feeding of birds helps spread disease, reducing their populations, the other is that feeding birds is boosting the populations of those birds that take advantage and disadvantaging birds who don’t. Furthermore, the population of Marsh Tits is not only stable but slowly increasing, even if one of the authors of the British Birds paper described it as “insignificant”. I have already refuted that, although I doubt he will have read it: he doesn’t like data that doesn’t support his prejudices.

My theory is that any increase in Blue Tit numbers is almost entirely down to the provision of nest boxes, not feeding, because, by supplementary feeding, those species that don’t participate have less competition for natural food sources. Neither is scientifically valid without further investigation but I think that my opinion is plausible.

Our group has had a phenomenal year for Blue Tits in 2025: with a one-third increase in adults and pulli ringed. Again, I will be waiting for the release of the ringing figures for 2025 before I can be definitive. What I have done with the graphs is stick to full data, as much as possible. The figures I have published exclude pulli ringed, as that has only been a part of our activity since Jonny took over the Wiltshire Wildlife Trust sites at Green Lane Wood and Biss Wood and started ringing pulli there and a few other areas in 2023.

So to start, these are the basic figures:

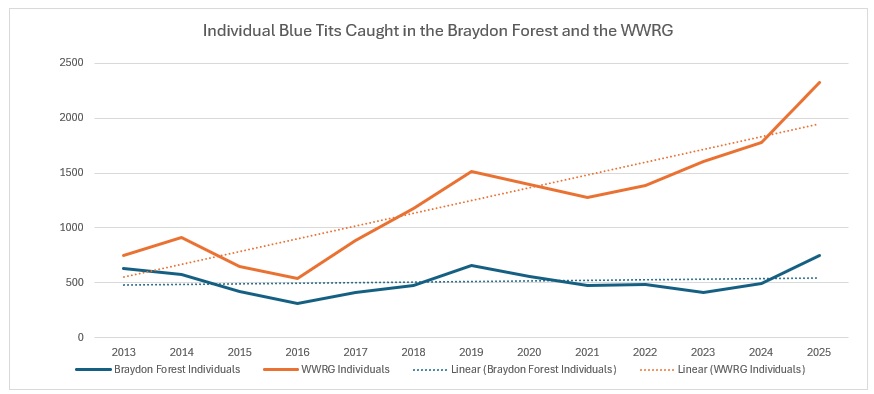

I have counted the number of individuals caught each year as well. This is a combination of every bird caught in the year, ringed or retrapped, but the ring number counted only once. Retrap data is not available for Wiltshire or England as a whole, so I am not able to include them.

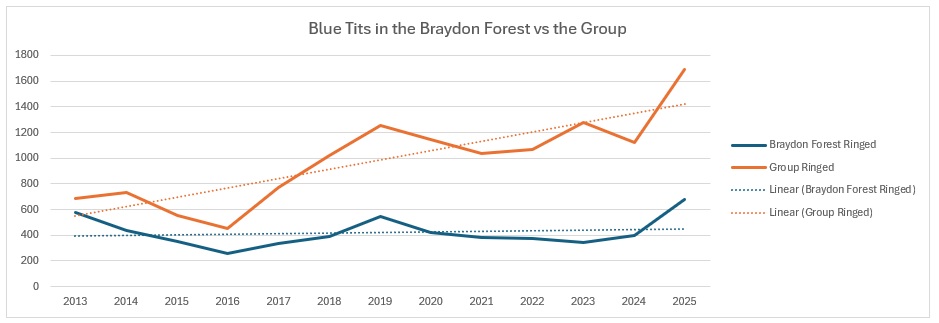

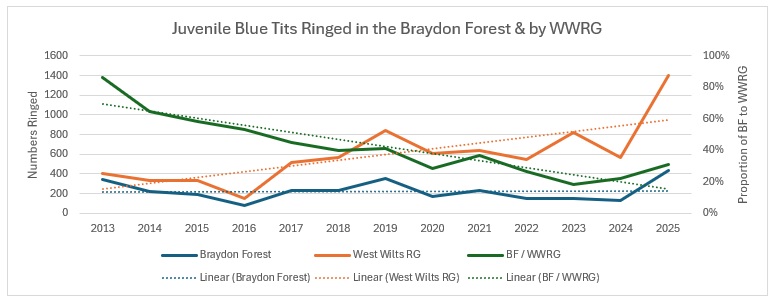

Let’s start with the numbers of fledged birds ringed and how the population in the Braydon Forest vs the total ringed by the West Wilts RG by year:

It is pretty clear from this graph that the population trend in the Braydon Forest is very stable and that the trend is pretty static. When you compare that with the Group results it is clear that the rest of the group sites are showing a population expansion. A lot of that is down to Jonny taking on new sites. However, one of the key things about two of those sites and the Braydon Forest, is that they have large numbers of nest boxes installed for titmice, bats and dormice in those woodlands. Those two sites have over 88 boxes between them: 50 in Green Lane Wood and 38 in Biss Wood. Some of those boxes are intended for dormice, but Blue Tits are frequently found in those boxes. Whereas in the Braydon Forest we have no titmouse boxes, and most of the dormouse boxes have been removed from our ringing sites. However, between October and until the weather improves in March, I do supplementary feed all of my ringing sites, topping up once per week with peanuts and seed mixes. As Jonny does with his sites, so the only difference in our records is the lack of nest boxes in the Braydon Forest!

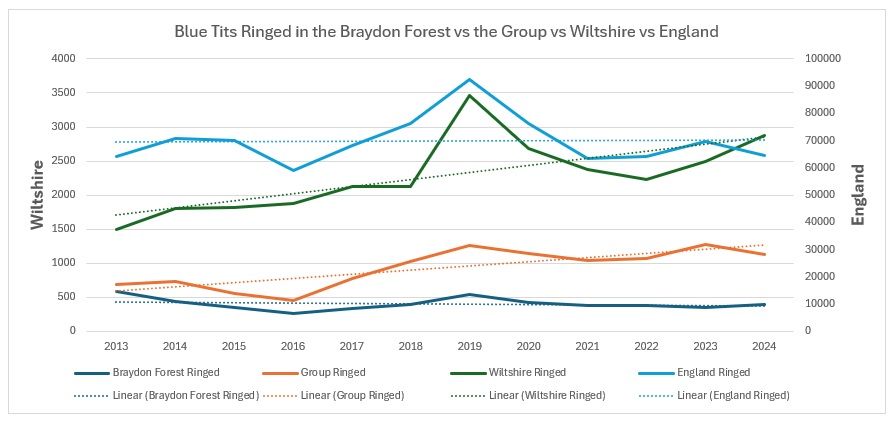

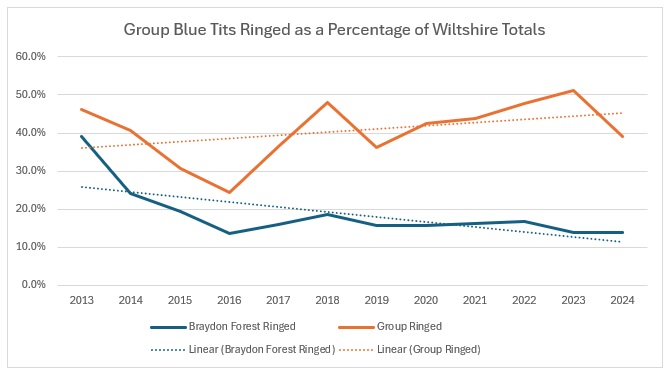

If we look at the ringing records for which we do have data for both Wiltshire and England, 2013 to 2024, it looks like this:

The interesting thing to note is that the trend line across England matches the trend line for the Braydon Forest, whereas the WWRG total matches the trend for the whole of Wiltshire (obviously, I have had to use separate axes because the England numbers are huge). It is pretty clear that 2019 was a very good year for Blue Tits, although the bulge is somewhat less for the group and even less so for the Braydon Forest.

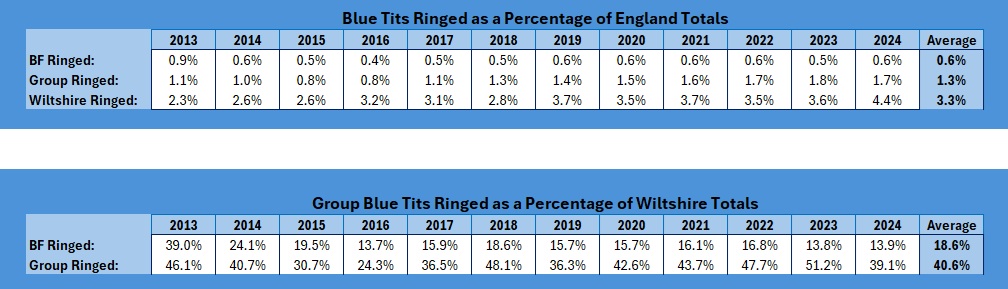

If you look at the totals on a proportionate basis, it gets more interesting:

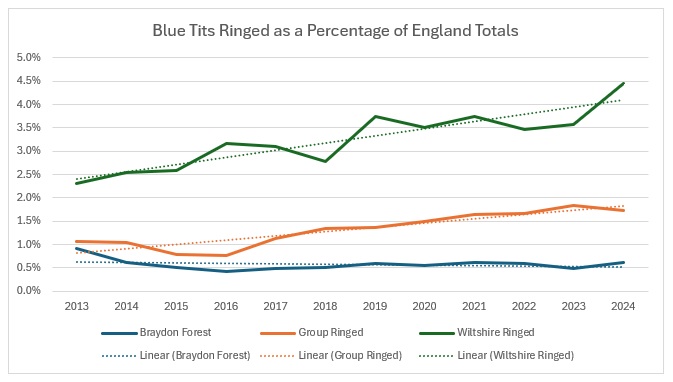

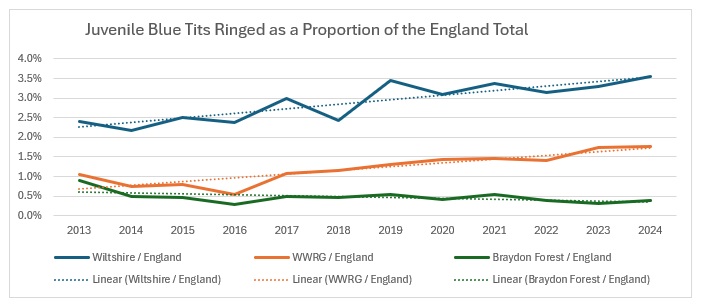

When we graph up how this looks, firstly as a proportion of England as a whole:

Again, it is clear that the Braydon Forest trend is stable, but also showing a slight decline. When we look at them as a proportion of the Wiltshire total:

The decline in the Braydon Forest against the increase in the Group is very much clearer when compared at this scale. Some of this will be due to the additional sites taken on outside of the Braydon Forest but, when you look at the overall picture, stability is the word in the Braydon Forest, whereas growth is what is happening across the Group and Wiltshire as a whole.

Where is this staggering increase in Blue Tits across the whole of England that is causing decline of other species? What does it say about the population of Blue Tits in the Braydon Forest, supplementary fed throughout the winter in the woodlands, and fed all year round in many of the local gardens? To me it says that the provision of nest boxes is a far bigger driver of population expansion than feeding. The paper that started all of this was produced by Shutt et al in September 2021. Their paper on establishing Blue Tit movements by taking faecal samples at known distances from the feeding stations identified that Blue Tits can move long distances. There were several things I found concerning about this study: there was no individual identification of the birds; so they did not know if it was one bird going backwards and forwards or many birds just passing through. If they did do this analysis, I could not find it in the paper they published, although the BTO ringing scheme was acknowledged. The other issue they did not address is the simple fact that they got their faecal samples from titmouse nest boxes they put up at known distances from the feeding stations and they took no account of the impact of providing nest boxes on the expansion of the Blue Tit population. At the time I stated regularly throughout my piece, that I wasn’t questioning their results, just that I was not finding the same situation in the Braydon Forest. That said, I did raise the question of not taking account of providing nest boxes for collecting samples. I have no wish to malign them, so you can read their paper here:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.2021.0480

I believe that the Edward Grey Institute of Ornithology use pit tags to monitor movements for their study: no need to provide nest boxes, just tags on the birds and receivers at the feeding stations.

In response to Shutt et al. I published an assessment of the movements in and out and around the Braydon Forest, and they are minimal. We do have the second longest movement of a Blue Tit ever recorded in the UK: AVF6109, ringed in the Highlands of Scotland in November 2019 and recovered in Ravensroost Wood in January 2022, a distance of 639km in just over two years. If you are interested in seeing just how minimal the movements in and out of the Braydon Forest are the link to my blog piece is below:

I have also had a look at the number of individuals processed each year in the Braydon Forest and by the Group as a whole. By individuals, I took birds ringed and retrapped, and counted each ring number split by year, counting multiple occurrences in the year as one and not the sum of them all:

The trend is very much the same as it is for the ringing numbers.

Finally, I have looked at the number of juveniles ringed in each year for our group and the Braydon Forest:

This shows the data up to, and including, 2025. As you can see, there is a stable situation in the number of juveniles ringed in the Braydon Forest over that period, despite the spike this year. When you look at the juvenile recruitment as a proportion of the Group, there is very clear decline within the Braydon Forest.

Looking at the trends as a proportion of the total juveniles ringed in England is quite informative:

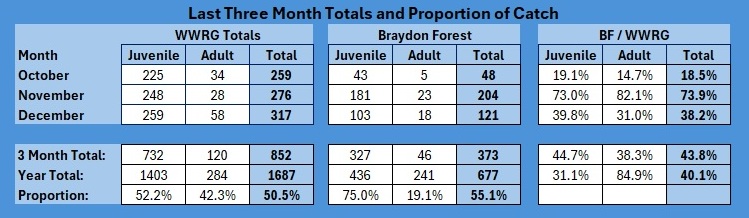

I have had to leave out the 2025 group data as I don’t have the values for Wiltshire or England to compare. Again, it just goes to show that the Braydon Forest situation seems to be very stable. It is somewhat surprising as in the last three months of 2025 we had our biggest catches of Blue Tits:

As you can see, we caught 55.1% of our entire Braydon Forest Blue Tit catch in those three months. What I find surprising is that, despite a 73% of the catch in November being juveniles, the sort of proportion I expect, but the rest of the quarter brought it right down just 31.1% of the Group’s catch in that period. Our proportion of the adults caught in that quarter is remarkable: nearly 85% of the entire Group catch! Over the year it seems that juveniles made up 43.8% and adults 40.1% of the Group’s annual catch.

To finish: I plan to keep monitoring the numbers and will update this post as and when I get the final data figures for 2025. One of the key reasons for carrying out this work was because both the Group and our little Braydon Forest project on Marsh Tits have generated some excellent results for that species this year, which I would contend, in the Braydon Forest, is down to the fact that there are very few artificial nest sites. I won’t spoil the surprise.