So, a final analysis in my four part Paridae examination within the Group, the subset of the Braydon Forest, and how they compare with the numbers for Wiltshire and England as a whole. This time it is our lovely Coal Tits, Periparus ater.

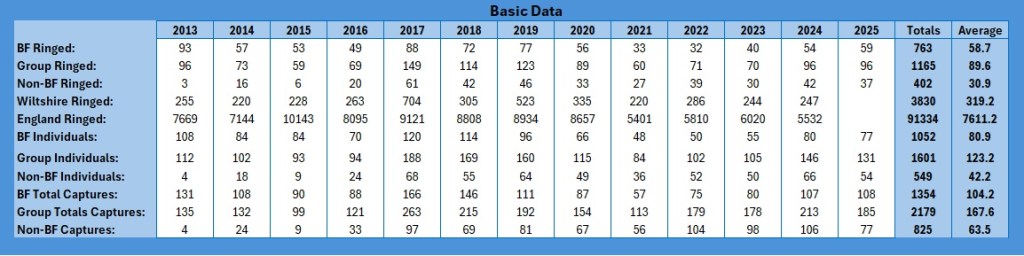

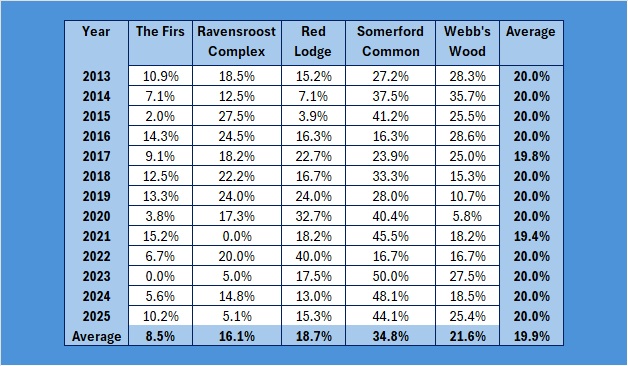

So, to start with, these are the basic figures:

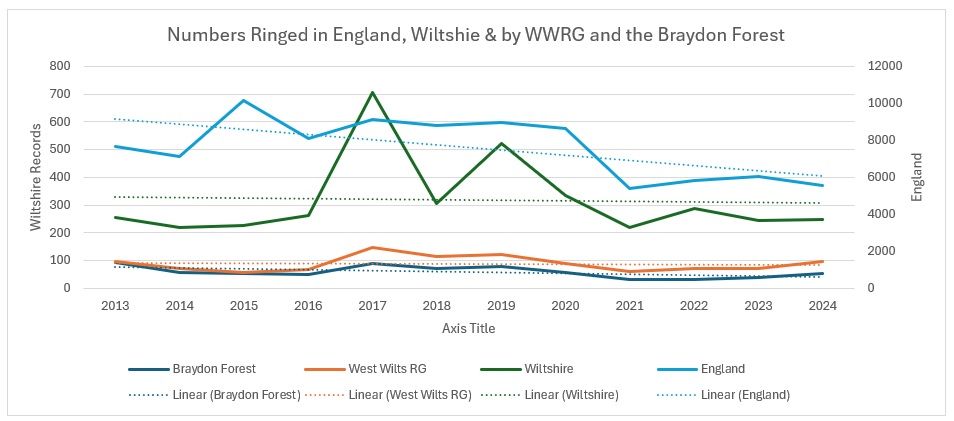

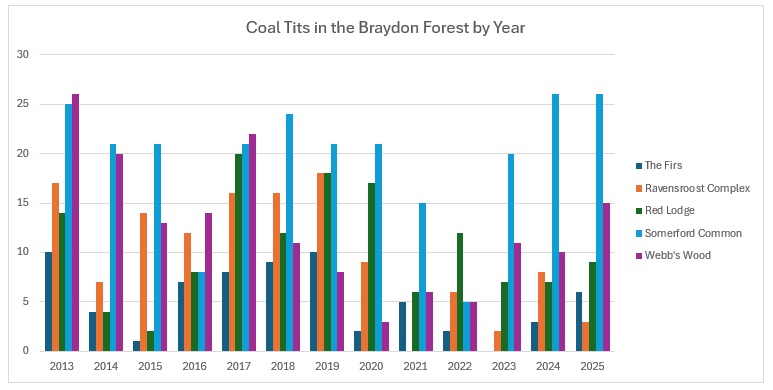

As with the other data sets, I have restricted the graphs to 2024 because the data for 2025 has not been released yet. So how do these basic figures look graphically?

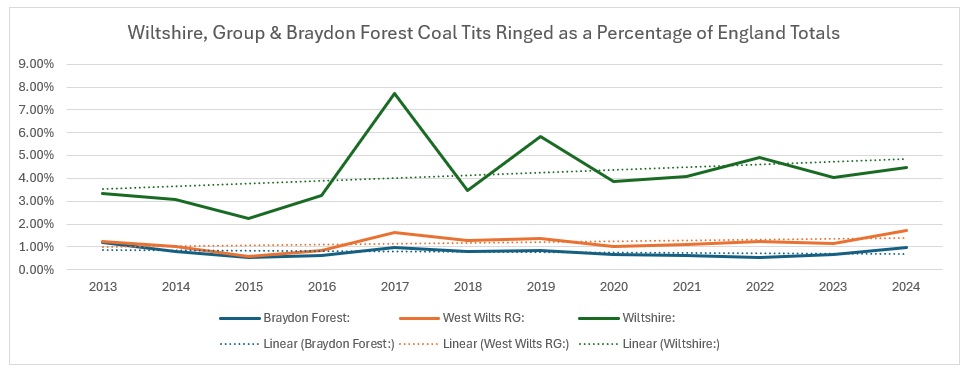

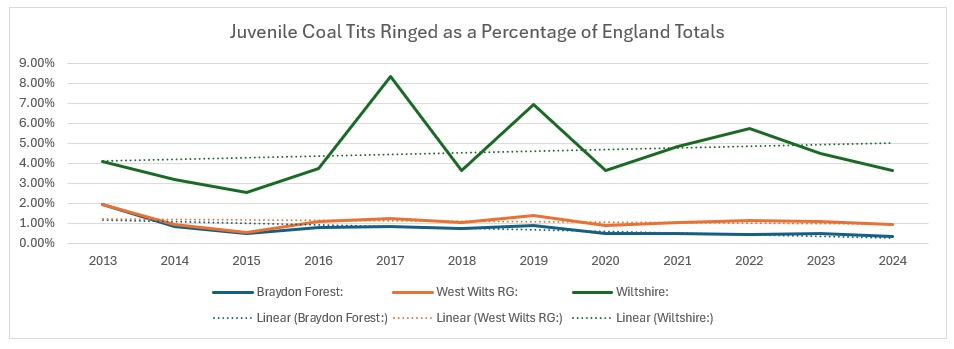

As you can see from the trendlines, the decrease across England is not as pronounced as it is across Wiltshire and within our group areas. As a proportion of the England catch it looks like this:

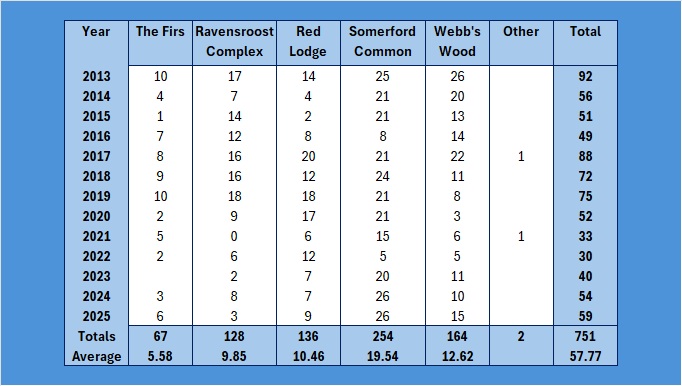

It is pretty clear that Wiltshire as a whole is bucking the national trend, whereas our group results show a slight increase, whilst the Braydon Forest is showing a slight decline. I am not sure why: the main site for them in the Forest is the Somerford Common complex and it is the one area that has undergone the least change over the 12 years of the study. Unlike the other four species, I decided to have a look how they split across the Braydon Forest:

Other is my back garden! As you can see, Somerford Common has the highest number caught over the years. Proportionately, it looks like this:

If you graph that up, it looks like this:

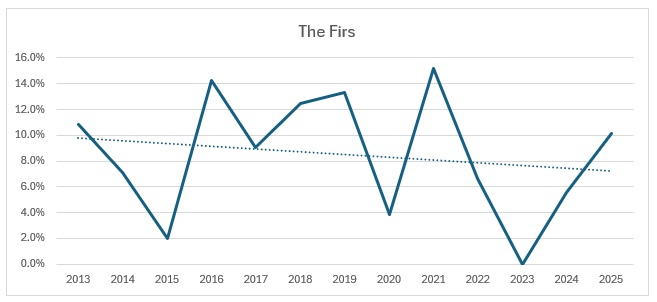

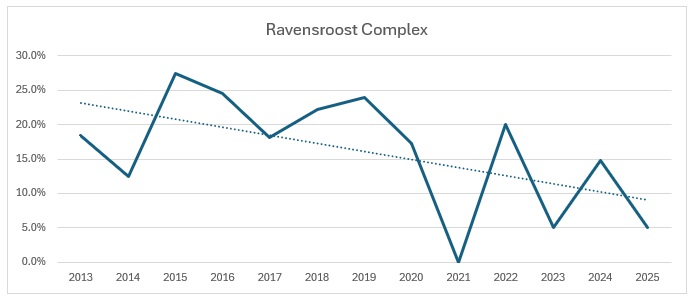

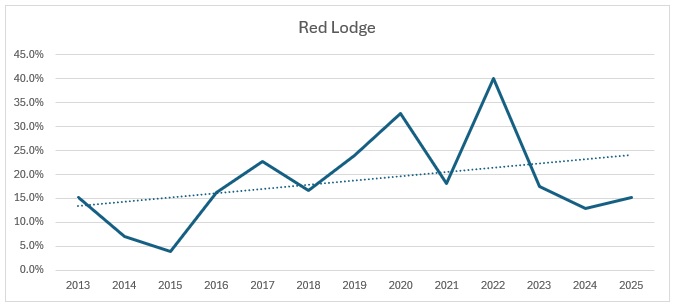

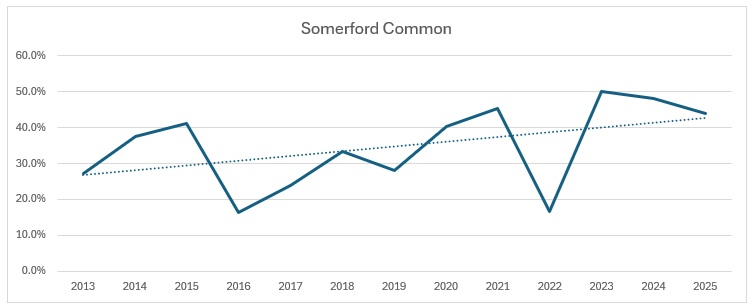

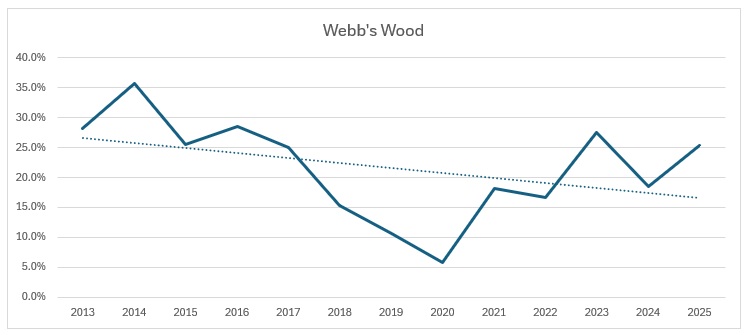

Far too busy to give an indication of where the decline might be, so I have split each out and produced trendlines for each site:

As you can see, the biggest decline is in the Ravensroost complex. followed by Webb’s Wood and the Firs. It just so happens that these three woodlands have all been undergoing significant forestry management over the years. Although Red Lodge did undergo some thinning operations a few years ago, it was in the eastern end of the wood and we work in the western end of the wood. Certainly it didn’t negatively affect the trend, which is a rise of 14% over the period, despite some very up and down results. Somerford Common is clearly the strongest site, also with a 14% rise in numbers over that period.

I am now going to have a look at juvenile recruitment. There is a caveat, of all four of the Paridae species, the Coal Tit is the most difficult to age. You look at the greater coverts and look at the outer fringing of the feathers: if they are blue grey it is adult, if it is yellowish it is juvenile. There is also a colour difference on the main feather body, but it isn’t always clear, the adult feathers being greyer, with a clear white square at the bottom right corner of the feather, when the bird is head away from you, whereas the juvenile feathers are generally duller and browner.

The numbers:

As you can see, the trend across Wiltshire is up and down but the trend is still positive, with an increase of 1% over the 12 years of the study. Our group results are looking stable but those of the Braydon Forest have decreased to negligible.

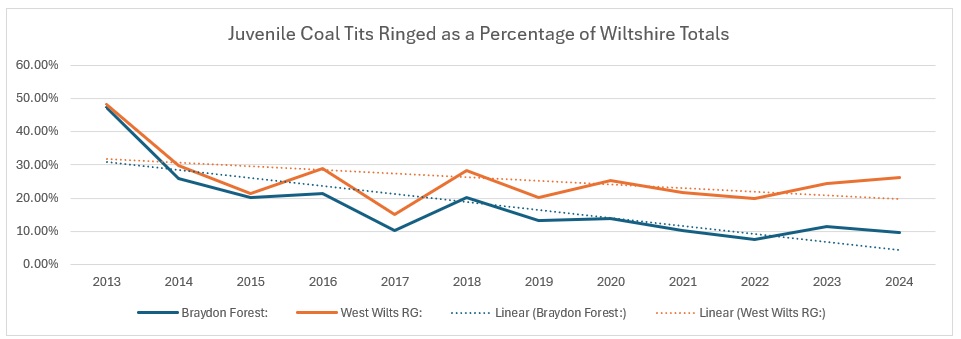

When looked at as a function of the Wiltshire numbers

When you look at the trend for the Braydon Forest against the Wiltshire catch, it make for even more depressing reading: from 30% of the Wiltshire total to just 4%. The group contribution, clearly affected by the decline in the Braydon Forest population, is not so bad, with a 10% decline from 30% to 20%.

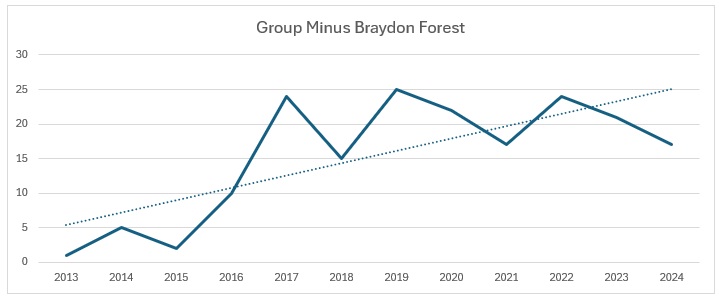

I then took out the Braydon Forest from our group results and the numbers look like this:

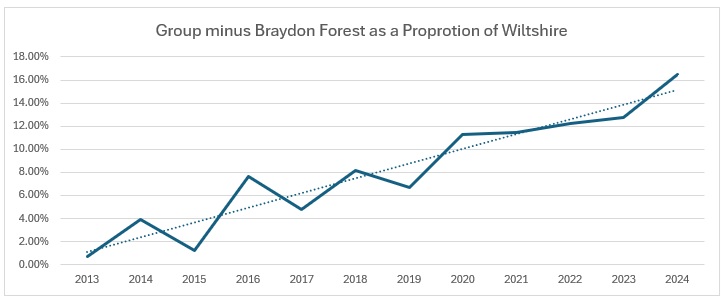

So there has been positive growth in the group numbers: still very small, which is why the impact is so pronounced. When the group’s activity is looked at as a proportion of the Wiltshire catch, it looks like a smooth increase, unlike the bald figures:

This increase in numbers is down to Jonny and Andy from our Group: Jonny taking on the Wiltshire Wildlife Trust reserves at Biss Wood and Green Lane Wood just outside Trowbridge in 2020, although their numbers had fallen away in 2024 and have done so again in 2025. In addition, Andy has caught good numbers at one of his Warminster sites in 2018, 2019 and, not as big as the other two, but a reasonable number in 2024. None of our numbers for the species are exceptional but there are a wide number of contributing sites, but not in any great numbers.

The worrying piece is why the decline in juvenile recruitment in the Braydon Forest has been so pronounced. If we can establish what that is we might be able to do something about it.