It’s raining, it’s pouring, no ringing, it’s boring! So I thought, having looked at the population levels of the Titmice being ringed in the Braydon Forest, whether these changes were reflected in the split between young and adults. To do this I counted all of the birds ringed with a BTO code of 3 and 3J for the year, and then I counted all of those ringed with a BTO code of 5 in the next year. For adults I counted all in the year with a BTO code of 2, 4 or 6. Not 100% accurate as a code 2 in a year means nobody knows when it fledged. This should only be an issue for species like Nuthatch, House Sparrow and Long-tailed Tit where both adults and juveniles moult into full adult plumage in the autumn. Everything code 2 becomes code 4 on the 1st January of the following year. , code 4 also applies to all birds, except codes 3 and 3J, once the breeding season is over and the post-breeding moult is under way. Code 6 means that they are definitely fully adult but, again, that reverts to code 4 after the breeding season. I have included figures for 2025, which is a little unfair as we will almost certainly catch more of each age group between now and June / July when the 2026 youngsters will fledge, so take those with a pinch of salt.

Blue Tit, Cyanistes caeruleus:

As the largest cohort of birds in the Forest, I started with Blue Tits. My previous post on their population in the Braydon Forest showed that it is relatively stable, but with a slow decline:

https://braydonforestringing.uk/2026/01/12/blue-tits-in-the-braydon-forest/

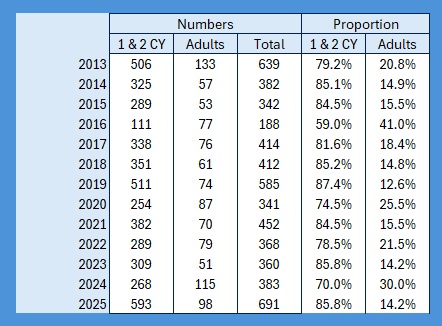

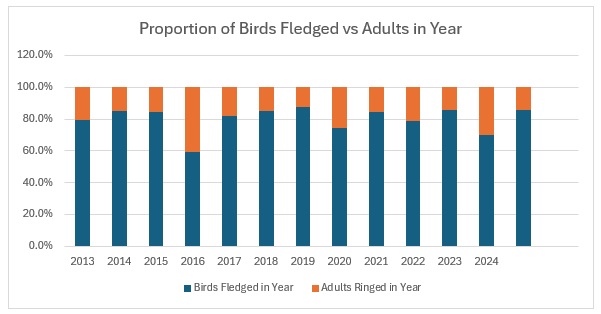

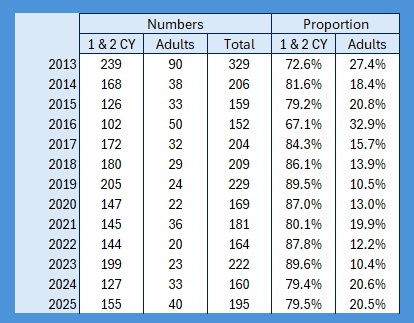

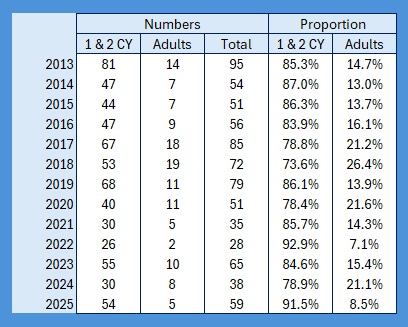

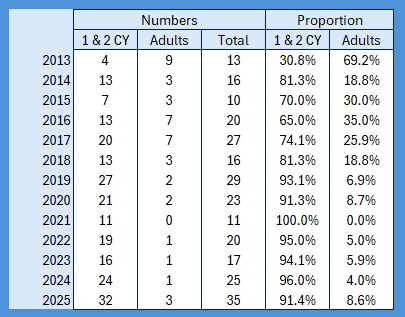

This is what I found:

When you graph up the basic numbers you see:

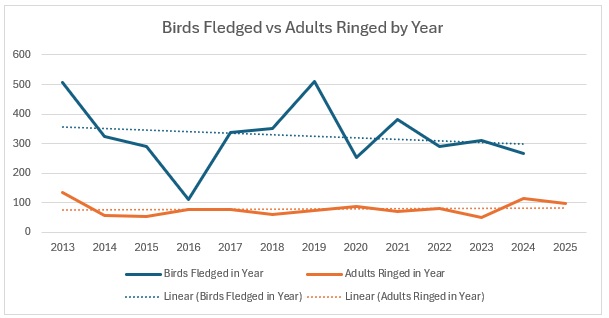

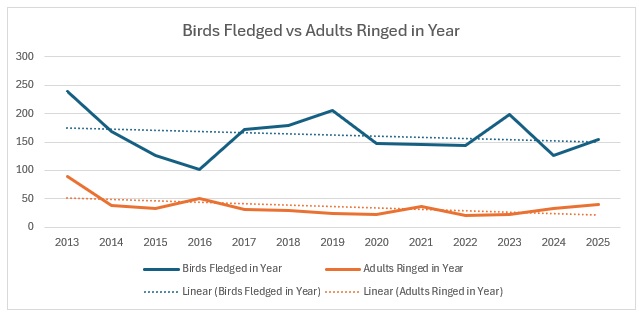

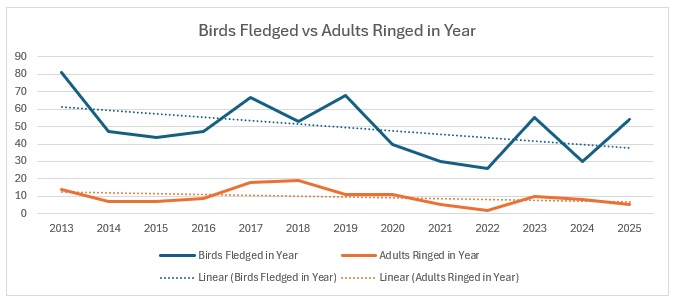

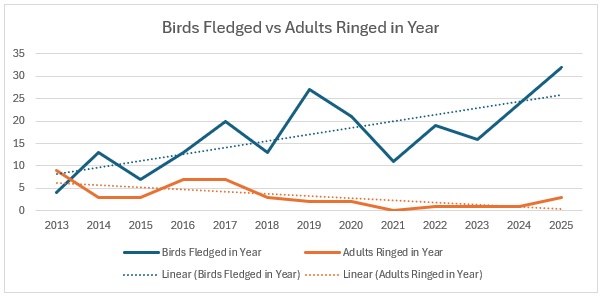

This shows clearly that 2016 was the worst breeding season for this species in the 13 years covered by the project. That shows in the stable trend line for adults but the decline in juvenile birds. When we look at the catch with juveniles vs adults as a proportion of the totals ringed we get this:

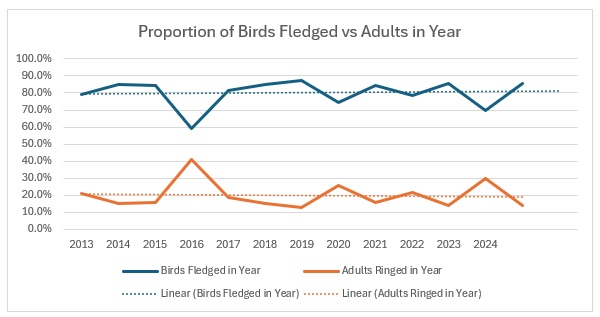

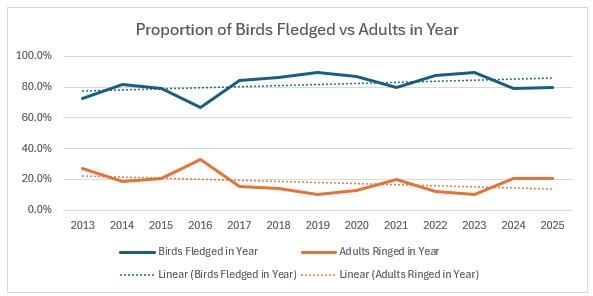

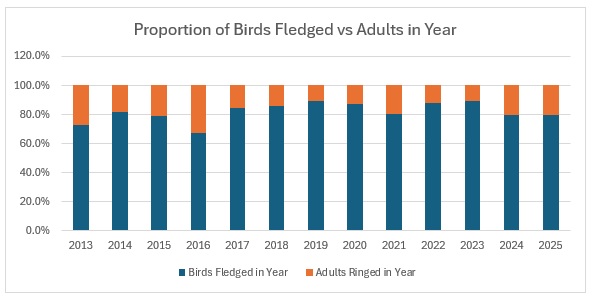

As you can see, across the entirety of the period, the trend in the catch is much more equivalent for both age groups than the numbers would indicate. The bar graph shows exactly the relationship between adults and juveniles:

The average split over the year is 80:20 and relatively stable, excepting 2016.

Great Tit, Parus major:

The previous post on the status of Great Tits in the Braydon Forest showed another species with something of a decline:

https://braydonforestringing.uk/2026/01/24/great-tits-in-wiltshire-wwrg-the-braydon-forest/

These are the basic figures:

Again, graphing up the basic figures shows:

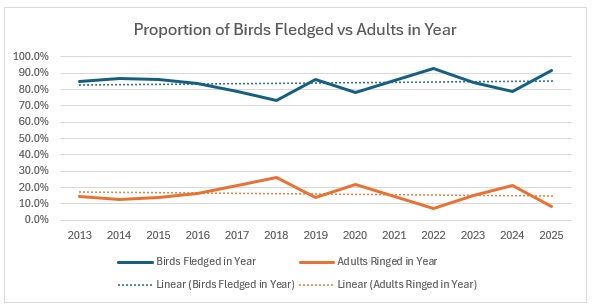

As you can see, both adult and juvenile numbers have declined in harmony with each other. When we look at the proportional analysis:

So, juveniles are increasing with respect to the number of adults being ringed. So, is the overall decline to do with a reduction in the number of adults surviving year on year?

As with the Blue Tit, the Great Tit clearly had a bad year in 2016, as the adults made up a higher than usual proportion of the total. Their average split though is 82:18, juvenile to adult.

Coal Tit, Periparus ater:

This species showed the biggest fall in [population over the period:

https://braydonforestringing.uk/2026/01/27/coal-tits-in-wiltshire-wrg-the-braydon-forest/

Looking at it in pure numbers, it does look as the key issue is adult survival. However, when you graph it up it is the juvenile numbers that show the bigger trend decline:

Proportionately, though:

Yet again, there is a slight increase in the proportion of juveniles to adults ringed across the period.

Again, as you can see, the proportions are largely juvenile birds. This time the ratio across the years is 84:16. Interesting to note that they were not affected in the same way as Blue and Great Tits in 2016, but did have a dip in the proportion of juveniles in 2018.

Marsh Tit, Poecile palustris:

Now to my key project species, to which I have already dedicated a lot of time, analysis and writing:

https://braydonforestringing.uk/2026/01/16/west-wilts-rg-marsh-tits-2013-to-2025/

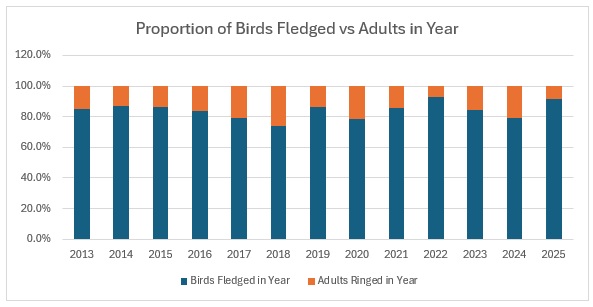

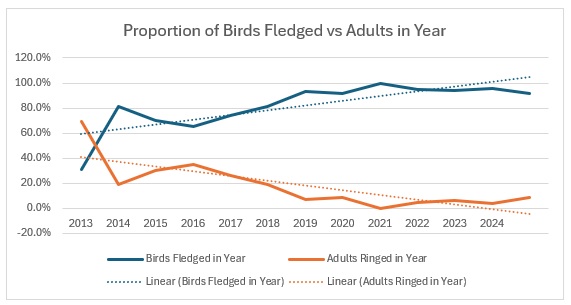

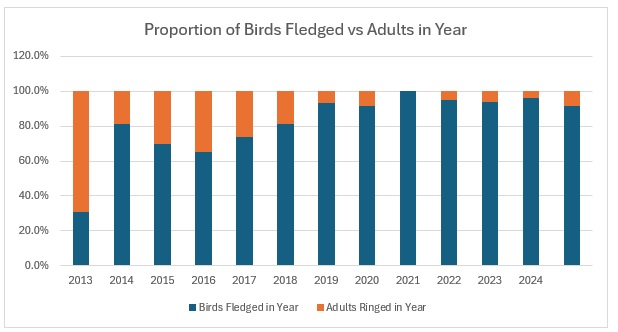

This is a real astonishingly different situation. Obviously, with a much smaller population, being a red-listed species, any changes are going to be amplified, so that needs to be borne in mind. However:

It is pretty clear what is happening here: juvenile survival is surprisingly strong, having started from a very low base, and adult survival is very much lower. Proportionately this is how it looks:

Obviously the concern is that, if we continue to have so few adults being caught, how long can the number of juveniles continue to increase?

I have absolutely no idea why the situation with Marsh Tits started with such a huge disparity between adults and juveniles in 2013. I hate to say it but perhaps my ageing capabilities for this species weren’t up to scratch in 2013, my first full year of solo ringing. (Then I purchased Jenni & Winkler: Moult and Ageing of European Passerines, the absolute bible of ageing, and have never looked back. First as a Kindle download and then the real thing when the second edition came out in 2020. Fabulous book.) Including that gives a proportion of 82:18. Excluding that year changes the proportion to 84:16. Obviously the unusual year was 2021: no adults ringed at all. I have never seen that in any of our regularly caught resident birds.

It is not that I am obsessed by titmice but they provide lots of data for looking at the health of our woodlands in supporting various bird populations.